Of all the teenage anxieties that can take root, beard growth – or the lack of it – was the one that really got to Vikram Arora. His facial hair was patchier than a drought-hit lawn and by the time he went to college he was very self-conscious. “You’d have older guys coming in with a bit of stubble and it was almost this guilty secret where I’d be thinking: ‘I wish I could have that,’” he says.

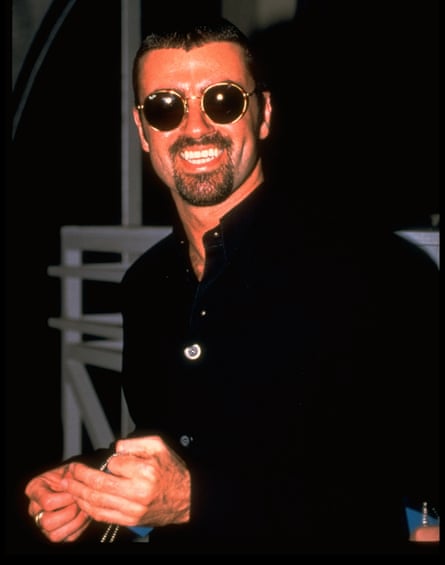

It was the 90s and George Michael’s sculpted goatee was everywhere. Arora, who is 47 and lives in Essex, remembers being racked with envy as he admired Tom Ford’s designer stubble in a photo in a clothes shop. At one point, he took to stealing his sister’s mascara wand in an attempt to fill in the gaps.

When Arora started a career in finance in London, facial hair wasn’t permitted in his workplace, but in the early 00s, he says, beards started to creep into the City as part of a wider outbreak of pogonophilia (love of beards). By 2010, Jason Statham, Idris Elba and David Beckham had become beard guys. At one point, three-quarters of Take That were bearded.

“Beards were even more trendy and I still had these sort of patchy whiskers,” recalls Arora, who resented having to shave every day, lest his sparse coverage reveal itself. “Through most of my teens and early adulthood, I was left feeling that I didn’t look mature enough – and definitely not masculine enough.”

I feel as if I almost don’t need to ask Arora what triggered the decision to do something about his facial hair deficit. For millions of people, the pandemic lockdowns in 2020 and 2021 created the compelling combination of spare time and disposable income, along with the harsh mirror of endless video calls. Demand soared for a whole gallery of aesthetic tweaks and surgical interventions.

Arora had heard about beard transplants a few years earlier. As much as he longed for facial hair, he also feared what might go wrong and that he would be judged for having had surgery. Come lockdown, which also prompted a surge in bigger, fuller beards, he was researching them obsessively. “Eventually, I said: ‘I’m going in for a consultation.’”

Arora ended up meeting Nadeem Khan, whose Harley Street Hair Clinic in central London has been doing hair transplants for more than 15 years. Beard procedures follow the same principle: surgeons use a needle to pull hairs, or “follicular units”, typically from thicker areas of hair at the back of the head. These grafts can then be inserted into less hairy areas of the scalp or face via tiny cuts in the skin.

Khan, the clinic’s chief executive, says follicular unit extraction was initially used only for beards on victims of trauma, such as soldiers with shrapnel wounds. His clinic would have half a dozen such patients a year. But as awareness of hair transplanting grew, thanks in part to celebrities such as Wayne Rooney, who restored his hairline in 2011, interest in beard restoration started to rise, before booming in the pandemic.

There are no industry stats, but Khan says inquiries from beard patients have tripled since 2020. His surgeons now do up to 100 transplants a year, 90% of which are aesthetic (the rest are fixes for scars or burns). Costs at his clinic range from £3,000 to £7,000, depending on the number of grafts. “I think there’s this new form of masculinity where the beard has become important and now every man wants to be like Gerard Butler in 300,” he says, citing the 2006 film.

Arora met Khan and one of his surgeons, Greg Vida, in 2022. In early summer 2023, Vida moved 780 follicles from the back of Arora’s head and planted them in his face. Just over £5,000 poorer, he went home with slightly reddened, swollen features and waited to see the results.

Arora’s fears about what could go wrong were well-placed. Rising demand for hair restoration has created a minefield for prospective and often vulnerable patients. Slick websites and social media accounts can obscure dodgy practices and sometimes scant observation of the regulations governing this type of work. Meanwhile, clinics in transplant-tourism hotspots such as Turkey have mushroomed, offering package deals that can cost a fraction of procedures in the UK.

Any hair restoration clinic in England must be registered with the Care Quality Commission. (Healthcare Improvement Scotland, Healthcare Inspectorate Wales and the Regulation and Quality Improvement Authority in Northern Ireland cover the rest of the UK.) Registration includes inspections, but there is no formally recognised training, nor any law that prohibits, for example, a clinic bringing costs down by allowing one doctor to oversee multiple transplants carried out by less qualified technicians.

“It’s still a wild west, this industry,” says Spencer Stevenson, a prominent mentor for balding men, who is known online as Spex. Stevenson says beard transplants are technically challenging. Head hair can be finer and softer than facial hair, requiring careful blending of hairs in thin or patchy areas to achieve a uniform look. The stakes are higher. “You can have a bad hair transplant and sometimes get away with it, but with a beard it’s a whole new kettle of fish because it’s on your face,” he says. “You can’t put a hat on it.”

Evidence of male insecurity around facial hair abounds online, where any prospective transplant patient starts his journey. Reddit’s public “beards” message board has 1.2 million anonymous members. Most posts feature images of fabulously bushy beards and maintenance tips, but it’s also a place where the less hirsute seek advice. In one typical post, a man with a big beard asks if he should get a transplant to fill in a gap below his lower lip. “I like my beard, but I’m always insecure about this area. I am 24,” he says. (Dozens of men tell him his beard is great already.)

Some posters move on to Reddit’s HairTransplants forum, where there are frequent pictures of completed procedures. One post includes a selfie of what looks like a great beard. Its owner is worried it creeps too high up his cheeks. “Am I stuck like this for ever? Is there anything I can do to help myself?” he asks. Again, the replies are supportive. “Dude, it looks fantastic!” one man says.

In a separate post, a man asks desperately about transplant reversals. It’s possible to pull out or laser bad grafting, but there is a risk of scarring. He lists dozens of problems with his surgery, including scars and poorly matched hair. “I literally don’t recognise myself any more,” he writes. “For the first time in my life I suffer from severe mental health [problems] … The stupid thing is I was always happy clean shaven. I just got greedy and tried to cheat my look.”

In March last year, Mathieu Vigier Latour, a 24-year-old student from France, travelled to Istanbul for a beard transplant. For just over £1,000, he received 4,000 grafts from the back of his head. “When it started to grow out, it looked like a hedgehog; it was unmanageable,” his father, Jacques Vigier Latour, told the French broadcaster BFM TV.

Stevenson says perfecting the growing angle of transplanted hairs to achieve a natural-looking pattern in a new beard requires skill. Latour’s growth was badly mapped and haphazard. His surgeon turned out to be a moonlighting estate agent.

Latour took it badly. “He was suffering, he wasn’t doing well,” Latour’s father said. “He was in pain, suffered from burns, and he couldn’t sleep.” While a Belgian transplant specialist was in the process of trying to fix Latour’s beard, he developed a kind of post-traumatic shock and body dysmorphic disorder, according to his father. Three months after the botched transplant, he killed himself. “He had entered a vicious circle from which he could no longer escape,” his father said.

Greg Williams, a former burns surgeon who switched to hair transplants in 2012, says surgery is often not a good option for men with a significant lack of coverage. “There’s a very high risk that a transplant won’t look natural if you’re talking about doing a full face,” says Williams, a specialist at the Farjo Hair Institute, which has branches in London and Manchester. He also warns men with alopecia against seeking a quick fix for new bare spots, given the risk that transplanted hair will also fall out.

Williams is a former president of the British Association of Hair Restoration Surgery, which promotes better practice. As well as the risks involved with transplant tourism, it has warned of the rise of illicit clinics in the UK, and hard-selling agents who take commissions for procedures without offering patients a chance to meet surgeons. The specialists and experts I speak to advise prospective patients to check the credentials of a surgeon directly, seek out patient testimonies, attend face-to-face consultations, view heavy discounts with suspicion and ensure that any transplant won’t be one of several supervised on the same day.

“It’s clear there is a black market and that there are untrained people who just use patients to make money,” says Özlem Biçer, a hair restoration surgeon who has been operating in Istanbul since 1998. She and her team treat only one patient a day and her prices are comparable with those of surgeons in the UK. “But the black market is a problem all over the world, not just in Turkey.”

Biçer performed her first beard transplant 20 years ago, on a man with facial scarring. She, too, has noticed a rise in demand, although she works on only half a dozen or so beards a year. She agrees that beard transplants are more challenging, partly because of all the nerves in the face, and says only experienced hair-transplant surgeons should take them on, after additional training. “If you’re not aware of what you’re doing, the complications can be more aggressive,” she adds.

Biçer says she has learned to gently advise vulnerable men not to go ahead. “If it’s about attractiveness or beauty, it’s OK,” she says. “But if it’s because he doesn’t feel like himself, or doesn’t feel like a man without a beard, you may not be able to make him happy.”

Like Arora, Franck Fontaine, one of Biçer’s patients, wished as a teenager that he could grow a fuller beard. He says it was largely an aesthetic problem, but that ideas of masculinity were in the mix. “For me, a man who didn’t have a beard didn’t look as virile as a man with a thick one,” he tells me from Réunion, the French island in the Indian Ocean, where he works as a nursery school teacher.

Initially, Fontaine, 32, felt that surgery wasn’t for him. But his father’s death in 2021 sparked something and he decided to make a change. Research led him to Biçer’s clinic; in 2022, he paid more than £5,000 to have 3,100 grafts moved from the back of his head over 12 hours. Three years later, the results, which I can see in our video call, are impressive. His full moustache is original, yet perfectly in keeping with the new hairs that now comprise his generous beard.

Fontaine kept quiet about the operation and says most people assumed he had just let his facial hair bloom. “Everyone was telling me how much it suits me and asking why I hadn’t grown it before,” he says. His six-year-old daughter, Maya, is the only naysayer. “I feel much more confident now, but she still tells me to shave it off every day,” he adds, laughing.

Back in London, Arora says that Vida deliberately introduced some asymmetry while placing his grafts, to avoid the forestry-plantation look that can give away a hair transplant. A few weeks after the procedure, he met some friends in a restaurant, having not told them what he had done. “I played it cool and didn’t want to say anything and they were just like: ‘What?!’” he says. “They were just staring at me, saying: ‘Bloody hell, that looks great.’ I’ll never forget that reaction. I was sitting there thinking: ‘Yeah, I pulled it off.’ One of them has always had a good beard and even he was saying: ‘Do you think I can make mine denser?’”

Arora now wears his beard proudly in the office. He regrets the way insecurity can lead men to take such drastic, costly action, but he sees his own transplant as an investment. “I invested in feeling good and you can’t beat that,” he says. His wife, however, couldn’t understand the fuss. “It makes no difference to her, but she can see that I’m happy now. A beard is a small thing for some people, but it has made a really big difference to me.”