This paper is the second in our “Inherently governmental” series that explores the U.S. federal government today. Over the past 80 or so years, federal spending has increased exponentially. Yet, the number of civil servants has remained more or less constant. The gap is explained by a large workforce of contractors. Opinions differ on the impact they are having on governance—is it bringing private sector efficiency to government or is it hollowing out the government? This series explores questions around what we define as “inherently governmental” work.

Understanding the size of the federal government

A major promise of President Trump’s second term is his determination to shrink the size of the federal government. Trump’s first move in this direction was allowing famed entrepreneur Elon Musk to lead an organization totally outside the government that would develop ideas for change and submit them to the Office of Management and Budget (OMB). Known as DOGE, the initiative quickly ran into feasibility issues. On January 20, 2025, President Trump issued an executive order which renamed the United States Digital Service, thereby placing its functions within the Executive Branch of the Government.1

Unlike the Trump initiative, the last large scale reform effort, Bill Clinton and Al Gore’s National Performance Review, was born within the government and focused on government performance as well as cost. They called their first report, delivered eight months into the new administration, “Creating a Government That Works Better and Costs Less.”2 The effort continued throughout the eight years of the Clinton administration and achieved both substantive and political successes.3 Many of the ideas pioneered during the last comprehensive review of the government, now more than 30 years ago, have since become standard operating procedure. For instance, back then, it was impossible to find information on a federal agency, complete a form, or conduct a transaction on the internet, and now this is standard operating procedure. The leadership of Vice President Al Gore—an early adopter of technology in public policy—allowed the government reform effort to cut layers of management and to move government online.

But 30 years later, there are new technologies to be taken advantage of and old regulations and statutes to be reviewed. Thus, as the second Trump administration assumes control of the government, it is time for another thorough look at the federal government. However, to be successful, the goals should be realistic. The initial goals of DOGE were not. At a rally at Madison Square Garden in New York on Oct. 27, 2024, Elon Musk said he would cut the budget by “at least two trillion” over an unspecified period. Many observers, including this author, pointed out that the entire current discretionary budget was only $1.7 trillion and that focusing on the size of the civil service or cutting regulations would not generate nearly the $2 trillion in savings anticipated at the start of the Trump administration.4 The largest portion of federal government spending is on entitlements like Social Security and Medicare, historically referred to as “the third rail” of American politics since the shock back to those who try to cut these gargantuan programs is often fatal. By early January, the real numbers had begun to sink in, and Musk admitted publicly that there “was only a ‘good shot’ at cutting half that.5

So, to begin, today’s government reformers must understand what the federal government is today. The first issue concerns the actual federal workforce. In 2014, John DiIulio Jr. wrote a brief but provocative book titled “Bring Back the Bureaucrats.” Since 1960, annual federal spending (in trillions) has increased exponentially, but the number of federal civilian workers has remained largely unchanged. In fact, as recently as the 1996 presidential campaign, President Bill Clinton bragged that, in his first term, he had created the “smallest government since John F. Kennedy was president.”6 As DiIulio points out, to understand the size of the federal government, one needs to put it in perspective. Over time, the federal workforce (full and part time) has shrunk as a percentage of the total U.S. population, from 1.1% in FY 1967 to 0.6% in 2018. In absolute terms, the federal workforce is slightly smaller than it was 50 years ago, even though the U.S. population has increased by two-thirds during that time period.7 Not only are the number of federal employees small compared to the population, but they also don’t cost very much. Compensation for federal employees cost $291 billion in 2019, or 6.6% of that year’s total spending.8

When it comes to the cost of wages and salaries, John D. Donahue found that “the private and public sector workforces now diverge sharply at the top and bottom of the earnings ladder.”9 Some of this divergence has, for instance, been the result of huge earnings at the top of the private sector. For example, consider this: Is there any private-sector CEO in the world who runs a company distributing $1.5 trillion annually in benefits to 66 million people, manages a workforce of about 61,000 employees, and oversees 1,500 offices globally, while earning less than $200,000 a year? The answer is no, but that’s the salary of the head of the Social Security Administration.

The relatively small size of the government payroll becomes even more striking when examining the workforce by education level. What once was a government of clerks filing everything from payroll data on American workers to military service records has been replaced by computers. Today, the federal workforce is composed of highly educated individuals. In 2023, 53.8% of the federal workforce held a four-year college degree or higher, compared to 40.4% of the overall U.S. labor force, and 21% had an advanced degree.10

The following table illustrates that at the highest education levels—those with a master’s, professional, or doctorate degree—federal employees earn less than their private-sector counterparts.

The majority of federal employees work in defense and security-related agencies; civilian employees at the Department of Defense agencies alone account for about 36% of the civilian federal workforce. They provide paychecks, health insurance, training, housing, and even run a school system for service members stationed abroad, supporting over 1.3 million active-duty personnel and nearly 800,000 reserve members.11

Federal civilian employment has stayed the same since the mid-1960s, even as the U.S. population has grown by 68% and federal spending has quintupled, adjusted for inflation. At the same time, the government’s work has become far more complex, including the creation of entire new agencies. This raises the question: How has the federal government managed to spend so much more money on a much bigger population with roughly the same number of federal workers as it had half a century ago?

The answer to the above question is twofold. Information technology definitely plays a role. Just keeping track of the earnings records of millions of Americans so that they can qualify for Social Security or keeping track of military service so that people can apply for benefits used to require thousands of clerks—now that data is computerized. But technology is not the complete answer. The fact is there is an enormous contractor workforce doing the work of the government. Lack of transparency surrounding federal contractors means that the exact size of this workforce is impossible to measure precisely. In many cases, contractors do more or less the same work as federal employees, and they often work in government offices and use government email addresses. In one important government office, green badges and blue badges differentiate the contractors from the civil servants, but they all work in the same place and on the same things.

Federal contract managers are too few in number and too outgunned in skills to manage it all. Writing in the Washington Monthly, Donald F. Kettl and Paul Glastris suggest that the president needs to issue an executive order to calculate the total size of the workforce supporting the government’s work.12 Until that happens, we don’t really know how many people work for the government, but Paul Light estimates that private contractors working for the federal government now outnumber federal employees by a factor of more than two to one, and that the true size of government is nearing a record high.13 As DiIulio points out, today’s federal government is composed of many more contract and grant employees than civil servants. The result, according to DiIulio, is “Leviathan by Proxy” —a federal workforce that he describes as unaccountable and a “grotesque form of big government that guarantees bad government.”14

This raises the question: Where are contractors performing government work, and is it a problem? Does this part public, part private workforce make sense in terms of function, performance, and democratic accountability?

In their book “The Big Con,” Mariana Mazucatto and Rosie Collington make the case that excessive reliance on outside consultants with extractive business models is stunting state capacity and undermining democratic accountability, although these problems are implicit rather than explicit. They cite a British Cabinet officer who charged that outsourcing government functions not only provides poor value for money but also “infantilizes the civil service by depriving our brightest people of opportunities to work on some of the most challenging, fulfilling, and crunchy issues.”15 On the other hand, Dorothy Robyn, writing for Brookings, argues that the use of contractors in non-combat roles within the U.S. Department of Defense to provide military housing provides better service and better value without diminishing the Department’s warfighting abilities. As one congressman put it, “I want Marines focused on bullets and bad guys, not managing HVAC systems.”16

Who is right? Are contract workers infantilizing the civil service, or are they allowing civil servants to focus on the core mission? The answer is somewhere in between. The first step in addressing these fundamental questions is to figure out where the problem is. The two charts below show the ratio of people who work on federal grants or contracts and the number of federal civil servants. As is evident from the following graph, the number of contract and grant employees exceeds the number of civil servants, military personnel, and postal workers by a significant amount. This is not a new development, but the trend in the second decade of the 21st century shows a shift toward an increasing reliance on contract workers.

This new workforce—part public and part private—has been summed up in many ways; Paul Light calls it the “blended” workforce; John D. Donahue and Richard J. Zeckhauser refer to it as “collaborative governance”; Elaine Kamarck has written about “government by network”; and William D. Eggers and Donald F. Kettl have written about “bridgebuilders.” Whatever you call it, it is here to stay, yet we know very little about it. It is difficult to determine exactly what work is being contracted out and why, making it challenging to assess whether “inherently governmental” functions are being performed by the private sector.

But the question remains: Is today’s federal workforce writ large a problem? Frankly, it depends on what kind of work the contractors are doing.17 In order to evaluate whether contracting out is a problem, we need to understand exactly what the federal government is contracting out. According to a study by the Government Accountability Office, the Department of Defense accounts for nearly 60% of all contracts.18 The entire rest of the federal government accounts for around 40%. One of the reasons that the Defense Department spends so much on contracts is that it buys a lot of expensive hardware, including tanks, guns, ships, bombers, and modern space-based systems. The funding request for these systems alone totals $315 billion in 2024—more than the contracting costs of the entire rest of the federal government. The five largest defense contractors employ about 655,500 people—thereby accounting for a large portion of contract workers.19

But is this a problem? No one seriously promotes creating government bureaucracies to build bombers, ships, and tanks—despite regular scandals and cost overruns involving military contractors. On the whole, the American tradition of contracting out weapons procurement has been a big success. Because we brought the private sector into the building of tanks, airplanes, and weaponry, we were able to supply large amounts of weaponry to our allies during World War II. But as the war progressed, then Senator Harry Truman (D-Mo.) took on war profiteering and placed controls on contractors. And during the Cold War, both the Soviet Union and the United States sought better weaponry. The Soviets made sure that every step, from research and development to production, was under control of the state, while Americans engaged countless corporations, universities, private laboratories, and government research labs to develop sophisticated weaponry. When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1989, we discovered that its technological and military capabilities had lagged far behind those of the United States.20

The basic problem is that while it is possible to determine the dollar amount of federal contracts and to estimate the number of employees involved in contracts, those figures alone don’t tell us whether contracting is taking place in ways that undermine government performance and accountability. For instance, we know that in FY 2022, $694.2 billion was spent on federal contracts and that most of the money was spent by the Defense Department. However, according to the Government Accountability Office, “The single largest contract among fiscal 2022 vendors was for the 10 million doses of Pfizer’s Covid-19 treatment Paxlovid, purchased by the Pentagon.”21 This was, hopefully, a one-time expenditure which did not prompt arguments for the federal government to take on the role of discovering new pharmaceuticals.

By looking at the Federal Procurement Data System, Nation Analytics was able to break down spending into two broad categories—service and products—as seen in the table below. Just as we don’t see the manufacture of weapons systems as something the government itself should be doing, neither do we see the research and production of medicines and vaccines as a core government function. The federal government buys a lot of things in order to do its many jobs—socks for soldiers, drugs for veteran’s hospitals, floor mats for federal buildings, computers for the State Department, and yellow legal pads for the Justice Department. One can argue about the costs or even the necessity of new fighter planes or expensive drugs, but no one argues that these should be manufactured by the federal government.

The concern about contracting comes from the “services” category, where critics have voiced two key issues over time. The first is that by contracting out certain services, the government is robbing itself of expertise and allowing that expertise to develop outside its ranks. The second is that, in combination with this lack of expertise, the sheer size of the contracts is straining the ability of the civil service to hold contractors accountable.

It is tempting to frame the problem as totally within the “services” segment of contracting, but even there, definitions can become murky. Take the business of feeding soldiers. The Defense Department regularly allows franchises like McDonalds and Burger King to operate on its military bases at home and abroad. Few would consider serving hamburgers as an “inherently governmental” function and critical to warfighting. But what about feeding soldiers in the middle of a combat zone? As the saying goes, “An army marches on its stomach.” In such cases, the cooks have to be trained and armed, and they may very well find themselves fighting and dying. In that context, feeding soldiers is essential to warfighting and cannot be contracted out to McDonald’s.

The challenge before us is to develop a framework for understanding the characteristics of “inherently governmental” functions, which has been central to determining what tasks should and should not be contracted out.

In 1966, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) published the first circular on outsourcing—dubbed A-76. Since then, A-76 has been amended many times. It seeks to define when a government function can or should be outsourced, with the central question being whether the function is “inherently governmental.”

However, the guidance fails to address the multitude of gray areas in government. One of the most thoughtful examinations of the problem was penned by Allan Burman, administrator for Federal Procurement Policy, in 2000. He writes:

“The difficulty is in determining which of these services that fall between the extremes may be acquired by contract. Agencies have occasionally relied on contractors to perform certain functions in such a way as to raise questions about whether government policy is being created by private persons. Also, from time to time, questions have arisen regarding the extent to which de facto control over contract performance has been transferred to contractors.”22

Going back several decades, I have been asked if government contracting out is good or bad. My response has often been the rather unsatisfying “it depends.” To break down the problem, we need a framework that provides more guidance than has existed in the past. First and foremost, to grasp the size and composition of today’s federal government, more research and better data are needed on what is being contracted out—particularly in the area of services, where the uncertainty around what is “inherently governmental” exists.

Second, we need a framework that takes into account the types of government work and accountability mechanisms, including both performance and contract compliance. The “broad brush” approach advocated by so many partisans simply doesn’t line up with reality. Put simply, sometimes government contracting makes sense, and sometimes it doesn’t.

As we have seen, the problem with the size of government is not the federal workforce, which has remained fairly stable for more than half a century in the face of large increases in federal spending and the U.S. population. Nor is the problem the dollar cost of contracts themselves. Much of federal contracting is on hardware, especially military hardware. Few would argue that it’s a good idea to have the federal government manufacture tanks, airplanes, guns, or soldiers’ socks. Thus, the real area for examination is the contracting out for services, and even here, important distinctions must be made. Contracting out services unrelated to core missions—like food service—may be good management, but contracting out oversight of contracts to consultants, for example, could lead to the “hollow government” about which so much has been written.23

Given that the Trump administration will be taking the first comprehensive look at government spending since the Clinton administration, a framework for understanding who should be doing what sorts of functions is critical. First, we need to understand that the U.S. federal government is not one entity. It is more like a gargantuan holding company, where the subsidiaries vary enormously in what they do. Some agencies, like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), try to track down the cause of health problems and outbreaks of disease. Others, such as the Department of Defense, train individuals to be ready to fight wars. Still others, like the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), send out checks to health care providers on behalf of those who qualify for care. That is just a small sample of the many missions within the federal government’s subsidiaries—one size does not fit all. The same goes for reform options. Secondly, in the private sector, accountability is often measured in dollars and cents, but in the public sector, each reform measure has its own system of accountability.

The four general categories of reform are:

- Privatization

- Contracting out or government by network

- Reinventing government bureaucracies

- Creating a market or government by market

This is a fundamental question for anyone engaged in government reform. Put simply, does the public sector really need to be doing this at all? In 1979, voters in Great Britain elected a conservative Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher. She came in with a radical agenda designed to revamp the stagnant British economy. She made the word “privatization” famous, and over the course of her 11 years in office, she sold many major businesses to the private sector, such as British Airways, British Telecom, British Steel, and British Gas.24 Following Thatcher’s example, countries around the world embarked on a wide range of privatizations.

However, privatization has never been an important strategy for U.S. government reformers for one simple reason—the United States has never nationalized large industries. Despite its name, American Airlines is not and has never been owned or operated by the federal government, nor has AT&T or many other U.S. companies. Even though President Ronald Reagan shared a strong preference for the private market with Prime Minister Thatcher, he succeeded in privatizing very few pieces of the government because, in reality, there were few to privatize.25

Privatization is not easy. Great Britain endured large, often violent strikes during this period, especially among coal miners. In more recent history, the newly elected president of Argentina, the right-wing populist Javier Milei, won his election promising to privatize many industries, including state-run media and the country’s largest integrated energy company. Trump advisors have already been looking to Milei as a model for their own work. But, once again, the targets in the U.S. are limited. Media companies in the U.S. have traditionally been privately owned. While National Public Radio receives some federal funding under a complicated statute, it is typically a target for Republican administrations and Republican Congresses. However, the majority of American media is private, not public.26

That said, there are still some targets for privatization in the federal government. One is air traffic control, a vital function in any modern economy. Privatization of air traffic control was floated and rejected in both the Reagan and Clinton administrations, but the idea is as relevant today as it was back then. Testifying before the House of Representatives’ Subcommittee on Aviation, Dorothy Robyn, an expert on the FAA, writes “…several dozen countries now provide air traffic control services through a self-supporting, autonomous agency outside of traditional government bureaucracy (in 1995 only a few countries did so.)”27 According to Robyn, these systems work well, while others argue that the governance structure of the American air traffic control system impedes what could be done more effectively outside of government.28

A second possibility for privatization is the U.S. Postal Service. USPS has been losing money since the early 2000s for two reasons: a 2006 law requiring it to prefund retiree health benefits and the rise of internet usage, leading to a decline in first-class mail. Initially, it was birthday cards and Christmas cards, but as companies began billing customers online rather than through the mail, volume dropped dramatically. While mail is often considered an “inherently governmental function,” many other countries have privatized their mail delivery. Portugal privatized in 1991, Germany in 2000, Japan completed a staged privatization in 2007, and the United Kingdom finished in 2015. Other countries with private postal systems include the Netherlands, Australia, and New Zealand.29

Privatization is not easy and can be very disruptive. For instance, in the United States, privatization of the postal service would almost certainly increase costs for people in very rural districts where the “last mile” is expensive to service. However, it remains an option for some government services.

In the United States, contracting out government work is more common than outright privatization. In earlier work, I have called this “government by network.”30 In government by network, the federal government makes a conscious decision to implement policy by creating a network of state or local governments and/or by creating a network of nongovernmental organizations through its power to contract, fund, or coerce. The variety of organizations that have been part of government by network is immense: churches, research laboratories, nonprofit organizations, for-profit organizations, and universities have all been called upon to do the work of government. The network model is most prevalent in the area of social services, but it exists throughout the federal government, hence the comparison to one big ATM machine.

Government by network offers one major advantage over traditional bureaucratic government: It allows many different organizations to address a problem. Take mental health and addiction, for example. The Department of Health and Human Services includes the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMSHA), established to help the United States tackle these issues. The agency’s goals are:

- Preventing substance use and overdose;

- Enhancing access to suicide prevention and mental health services;

- Promoting resilience and emotional health for children, youth, and families;

- Integrating behavioral and physical health care; and

- Strengthening the behavioral health workforce.31

One of SAMHSA’S key roles is funding programs like naloxone distribution to reverse opioid overdoses. No federal bureaucrats at SAMSHA are on the streets handing out naloxone; instead, that work is carried out by first responders, NGOs, and other groups. Similarly, SAMSHA employees do not provide counselling or treatment directly. Their focus is on administering “Grants to Prevent Prescription Drug/Opioid Overdose-Related Death, First Responder Training for Opioid Overdose Reversal Drugs, and Improving Access to Overdose Treatment.”32 The Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates that across the United States, 397,880 people are employed as substance abuse, behavioral disorder, and mental health counselors.33 However, in FY 2023, the work of SAMSHA was done by 722 federal civil servants. They give out and monitor contracts.34

Eliminating these grants or shifting the burden entirely to the private sector is an option often promoted by budget-cutting conservatives, who sometimes favor block granting programs to states under the guise of efficiency—though this often leads to funding cuts to the programs overall. But cutting the 722 civil servants who administer the grants wouldn’t significantly impact the federal deficit but would increase risks of waste, fraud, and abuse with fewer staff to oversee spending.

Government by network has the advantage of flexibility. Addiction treatment, for instance, requires tailored approaches, and attempting to standardize this service across a rigid bureaucracy would be foolish. If a network is managed properly (and that’s a big if, since they often are not evaluated properly), best practices could conceivably emerge. Beyond social services, research and development also benefit from this model. As mentioned earlier, one of the most successful examples of the use of government by network comes from the Cold War era. Seeking ever-better weapons against the Soviet Union, the United States engaged corporations, universities, private laboratories, and its own internal research laboratories in the development of sophisticated weaponry. In the kind of controlled experiment that rarely happens in the real world, the totalitarian Soviet Union kept its weapons research within its all-encompassing bureaucracy. By 1989, the experiment was over. When the Soviet Union fell, we learned, among other things, that its technological and military capacity had fallen well behind that of the United States. The U.S. approach of government by network had won, and bureaucratic government had lost.35

I’ve often described the federal government as one giant ATM machine for states, localities, and private organizations. Even churches, which are usually thought of as outside of government, depend heavily on government money to implement their poverty programs. For example, Catholic Charities, the nation’s largest provider of social services, has always been heavily dependent on government contracts.36 Today, about two-thirds of their annual budget comes from government sources.37

There are, of course, downsides to government by network. Fraud is a constant issue, and to prevent it, the government often places many regulations on their contractors, which can create new challenges. In an effort to prevent fraud, federal officials often tie providers up in bureaucratic knots. While the networks themselves don’t cost very much to administer, the administrative burden often reduces resources for evaluating the work of the network. This is unfortunate because the variety of organizations in a network—has the potential to teach us valuable lessons about what works and what doesn’t. Reformers looking at networks should seek ways to incorporate robust evaluation into the work of those in the network.

Accountability in government by network requires careful evaluation of the players in the network. Going back to the example of addiction and mental health services, accountability should be judged by comparing one organization’s results to another’s and periodically weeding out poor performers.

Government by network is useful for certain types of public policies but not for others. Some government functions have unambiguous goals and can be routinized, while others require a high level of security. When the two occur together, public bureaucracy is often the best approach. Issuing passports, driver’s licenses, or other forms of legal identification and determining eligibility for government benefits are two examples of policies that can be routinized and require high levels of security.

In theory, these functions could be performed by a network of contractors, but the stakes are too high. Legal documents are critical to identity and security, and government benefits involve large sums of money. For instance, many states use the network model for selling hunting and fishing licenses, allowing them to be sold in convenience stores or sporting goods stores. However, no one has suggested that private retailers, such as Dick’s Sporting Goods, should issue passports or Social Security cards.

That said, just because some areas of policy are best managed by government officials doesn’t mean that they can’t incorporate modern business practices—especially those that focus on delivering good customer service. A modern or reinvented public sector should embrace many of the strategies used in the private sector. The following is a list of the most common strategies used in high-performing private and public sector organizations:

- Creating and measuring customer service goals;

- Using technology to increase productivity;

- Using performance measures to guide management;

- Reducing regulations and emphasizing compliance in addition to enforcement for important regulations; and

- Creating and awarding an ethos of innovation and experimentation.

Many of these practices are now standard in federal government operations. The Government Performance and Results Act of 1993 mandated the inclusion of performance measures in the federal budgeting process, requiring agencies to provide performance plans and metrics in their budget submissions for nearly 30 years. Additionally, Executive Order 12862, signed by President Clinton on September 11, 1993, directed agencies that provide significant services to the public to establish customer service standards.38 These innovations have helped guide government management ever since.

One of the great paradoxes of the federal government is that, for decades now, Americans have been asked if they trust the federal government to do the right thing some or most of the time, and substantial majorities say no.39 And yet, when asked about how individual government agencies perform when citizens actually interact with them, citizens give the government high marks. The American Customer Satisfaction Index is a private company that surveys customer satisfaction in 10 economic sectors and 40 industries—one of which is the U.S. federal government.40 Every year, they survey Americans about their interactions with the federal government and ask them about performance in four areas: process, information, customer service, and websites. In their 2023 survey, satisfaction with the government scored 68.2 out of 100—an improvement over the COVID-19 years. Satisfaction ratings were slightly higher among Democrats (71) compared to Republicans (67) and Independents (66).

Technology advancements and innovations may lead to cost savings, though these savings will not be nearly enough to balance the budget. However, what they can do is keep the government from getting any bigger.

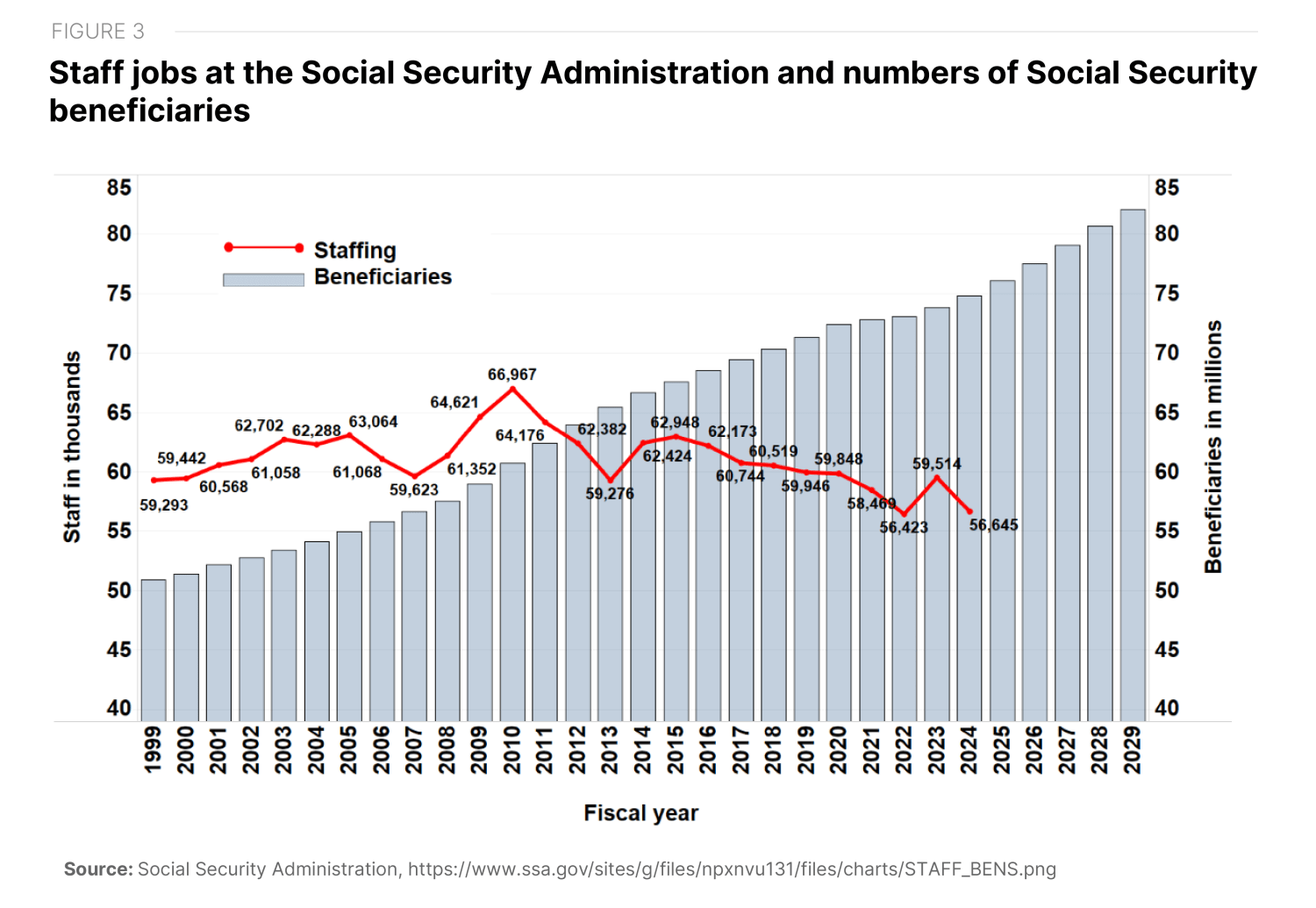

The following chart illustrates staffing levels at the Social Security Administration, which have decreased over the years from a high of nearly 67,000 in 2010 to 56,645 in 2024, even as the number of beneficiaries has risen significantly with the retirement of the baby boomer generation.

Fewer employees serving more customers can be a sign of efficiency—if, and that’s a big if—they can do it while keeping customers satisfied. By late 2023, Social Security was, according to The New York Times, in “a customer service mess that threatens to grow worse before it gets better.”41 Citizens seeking answers to their questions encountered long wait times on the phone and backlogs in applications for disability benefits. President Biden chose former Maryland Governor Martin O’Malley to straighten out the mess. Using his background in government reform, where he pioneered the use of the metrics management system, O’Malley was able to slash telephone wait times and begin a turnaround. However, when President Biden decided not to run again and Vice President Harris lost her presidential bid, his tenure ended.42

There are some things that simply have to be done inside the government, but there is no reason the public sector can’t adopt private-sector strategies (like strong customer service) to improve service delivery.

Accountability in a reinvented government can be measured by customer service metrics, cost per passport issued, or benefits enrolled.

There is wide agreement across the American political spectrum that well-functioning markets encourage efficiency and innovation. In government by market, the government uses its power to create a market with a public purpose that would not naturally emerge in the private sector. Successfully creating these markets depends on getting the design right, which includes setting the right price, ensuring the market is comprehensive and governed by the rule of law, and providing clear, accessible information about the market.

Most Americans already have experience with government by market. In 1971, Oregon passed the first container deposit legislation, known by many as the “bottle bill.” The goal is simple: Require a refundable deposit on cans and bottles so that people will return their empty containers to be recycled and reduce litter. Today, 10 states have similar laws, each with its own variation, but the general framework remains consistent. First, states must set an appropriate deposit amount—too low, and it fails to incentivize returns; too high, and it could drive up drink prices and face intense opposition from beverage companies, potentially defeating the legislation. Second, the program must include all containers, whether from Coca-Cola, Pepsi, or Budweiser—though some states exempt milk bottles. Everyone has to play by the rules, meaning the money promised must be returned to the customer. In some states, it is a misdemeanor for retailers to refuse to give back the money. And finally, the information must be easy to understand.

Bottle bills are an effective solution for reducing litter and promoting recycling, as they create an incentive structure that encourages widespread participation without requiring a government agency to employ hundreds of workers to collect litter. Over time, the concept has gained popularity among environmental advocates. In 1991, the Bush administration pioneered a market for sulfur dioxide (SO2) emissions, the primary contributor to acid rain. As part of the Clean Air Act, they established the Sulfur Dioxide Allowance Trading System, allowing polluters to buy and sell permits for emissions of sulfur dioxide. At first, environmentalists opposed allowing people to “pay to pollute,” but the well-designed market provided older coal-fired power plants with incentives to reduce emissions. As a result, acid rain—a significant environmental issue in the U.S.—has declined substantially in recent years.

The government-created market for sulfur dioxide was so successful that environmentalists attempted to create a market for fossil fuels. However, the cap-and-trade legislation, as it was known, failed during the Obama administration. While the sulfur dioxide market was fairly straightforward and easily understood, the cap-and-trade system was vast and complex. As the bill moved through the legislative system, it became mammoth and heavy with exceptions and special provisions, making it difficult to predict costs for consumers. Ultimately, the bill collapsed under its own weight.

In government by market, the accountability mechanisms are straightforward. Did SO2 emissions decrease over time or not? Did the highways have less litter or not?

Government reform is a complicated business, especially at the federal level. Because the federal government does so many different things, no one strategy fits all. As discussed in this paper, there are various approaches to government change, but the strategy must align with the mission. The following table sums it up.

If reformers carefully consider missions, they can match their means to ends and achieve efficiencies that save money. The complexity of modern governmental challenges should continue to drive innovation in policy implementation. If the United States can create new forms of government, secure the talent to lead them, and figure out how to hold them accountable, the next century should allow government to serve their citizens and save money at the same time.

-

Footnotes

- https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/establishing-and-implementing-the-presidents-department-of-government-efficiency/

- U.S. Government Printing Office, September 7, 1993. Note that the author ran the project for its first four years under the office of former Vice President Al Gore. In the second term, the project was run by Morley Winograd.

- Substantively it produced significant downsizing in federal government personnel, cuts in federal regulations and in agency regulations, reform of government procurement, the introduction of customer service standards to government agencies, and the use of the internet (new at the time) to streamline service. A more comprehensive accounting of the efforts can be found at https://govinfo.library.unt.edu/npr/whoweare/appendixf.html. Politically, it was a success as well. In his 1996 reelection campaign, former President Clinton bragged of having the smallest government since John F. Kennedy was president (referring to the number of civil servants in the government.) He won a solid victory in 1996. In 2000, the politics of the issue weren’t quite as helpful—Vice President Al Gore won the popular vote but lost the Electoral College vote in an election that turned on a very close vote in Florida.

- https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/politics-news/elon-musk-says-doge-probably-wont-find-2-trillion-federal-budget-cuts-rcna186924

- Ibid.

- Kamarck traveled with President Clinton in 1996 and heard him say this often as part of his stump speech.

- https://ourpublicservice.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/FedFigures_FY18-Workforce-1.pdf

- https://www.cato.org/blog/yes-cut-federal-government-its-workforce; https://www.cbo.gov/publication/56324

- Reviewed Work: The Warping of Government Work, by John D. Donahue, Review by Hal G, Rainey, Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 54, No. 4 (Dec., 2009), pp. 671-673 (3 pages).

- https://ourpublicservice.org/fed-figures/a-profile-of-the-2023-federal-workforce/

- https://www.cato.org/blog/yes-cut-federal-government-its-workforce; https://www.cbo.gov/publication/56324

- https://washingtonmonthly.com/2021/06/27/memo-to-aoc-only-you-can-fix-the-federal-government/

- https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-true-size-of-government-is-nearing-a-record-high/

- Templeton Press, 2014, p. 5

- Penguin Press Random House, 2023, Chapter 7

- Rep. Michael Waltz (R-Flo.), House Armed Services Committee, quoted in Dorothy Robyn, “’Privatization” of non-inherently governmental functions: Why public-private partnerships are so effective—and so rare—in the federal government, Brookings, June 13, 2024

- The first Trump administration drastically underestimated the cost of the government shutdown because they neglected to take account of government contractors being out of work: https://www.cnbc.com/2019/01/15/source-white-house-believes-shutdown-will-be-twice-as-costly.html

- https://www.gao.gov/blog/snapshot-government-wide-contracting-fy-2022

- https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R47751

- See for instance, Roald V. Sagdeev, The Making of a Soviet Scientist: My adventures in nuclear fusion and space From Stalin to Star Wars, (New York, Wiley, 1995.)

- Ibid.

- https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/ETA/advisories/UIPL/2000/UIPL12-01a2.pdf

- One of the earliest works on this is American’s Hollow Government: How Washington Has Failed the People, by Mark L. Goldstein (Irwin Professional Pub, 1992)

- https://www.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/serials/files/cato-journal/2017/2/cj-v37n1-7.pdf

- The Reagan administration looked at privatizing the U.S. Postal Service, Amtrak, the Tennessee Valley Authority, and the air traffic control system but did not succeed.

- https://thehill.com/opinion/campaign/3950550-the-truth-about-nprs-funding-and-its-possible-future/

- https://transportation.house.gov/uploadedfiles/2015-03-24-robyn.pdf Among the countries that have private air traffic control are, Canada, The United Kingdom, Germany, New Zealand, and Australia.

- Ibid.

- https://www.gao.gov/assets/t-ggd-96-60.pdf

- See: Elaine C. Kamarck, The End of Government…As We Know It: Making Public Policy Work, (Boulder Colorado, Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2007)

- Department of Health and Human Services Fiscal Year 2025: Substance Use and Mental Health Services Administration, Justification of Estimates for Appropriations Committees

- Ibid, page 4.

- https://www.bls.gov/oes/2023/may/oes211018.htm

- Opcit, Department of Health and Human Services fiscal year 2025.

- See, for instance, the story of a Soviet scientist’s experience with the system in Ronald V. Sagdeev, The Making of a Soviet Scientist: My Adventures in Nuclear Fusion and Space from Stalin to Star Wars (New York: Wiley, 1995)

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1995/02/22/churches-may-not-be-able-to-patch-welfare-cuts/7785fe4f-b602-407c-832f-29bfff1c2d39/

- https://www.philanthropyroundtable.org/almanac/catholic-charities/#:~:text=Today%2C%20about%20two%20thirds%20of,dollars%20of%20federal%20grants%20alone

- https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/executive-order-12862-setting-customer-service-standards

- https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2024/06/24/public-trust-in-government-1958-2024/

- https://theacsi.org/company/history/

- https://www.nytimes.com/2023/12/02/business/social-security-phone-line-budget-cuts.html

- See: Martin O’Malley, Smarter Government: How to Govern for Results in the Information Age, Esri Press, 2024.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).