MEMOIR / MARCH/APRIL 2025

Nazi Persecution Scattered My Family. A Lost Archive Brought Us Together

How 10,000 pages of documents sent me on a journey through Germany’s dark past

BY TIMOTHY TAYLOR

PHOTO ILLUSTRATION BY ANA LUISA OJ

Published 6:30, JANUARY 27, 2025

I‘m in the airport in Vancouver, waiting for my flight. I’m off to Frankfurt to lay Stolpersteine memorial stones for six members of my family who survived the Holocaust, including my mother. I feel vaguely unsettled. Looked at one way, I’m heading over for a celebration of life, with cousins from my mother’s side gathering for the first time in decades. But as the far-flung diaspora of the Kuppenheim clan reassembles—coming in from Ecuador, Canada, Switzerland, and various parts of Germany—it’s also a grim reminder that the entire family was once very nearly destroyed.

The trip music of choice is Ein deutsches Requiem by Brahms, whose Jewish sympathies were noted by the sneering Wagner fan bros of his day. His example feels about right given the far-right political shadows lengthening in our world. Plus, Brahms also wrote the most uplifting funeral music I’ve ever heard, the chorale at the end of the third movement in particular, rising to a defiant climax.

But the souls of the righteous are in the hands of God

And there shall no torment touch them.

Perhaps these words from the Hebrew Bible’s Book of Wisdom are my best guide as the sky goes indigo blue over the Pacific, as the call to my gate goes out, as we file aboard and find our seats, the lights along the taxiways and runways beginning to twinkle and beckon. After all the planning, all the correspondence with Stolpersteine officials about the six brass cobblestones to be placed where these people last lived in peace in Germany—my grandparents Felix and Gertrud; Felix’s brother, Hans, and Hans’s wife, Ilse; Felix’s children, my aunt Traute and my own mother, Ursula—perhaps what I’m really doing here, returning to the scene of those long-ago crimes, is convincing myself that these six loved ones are at last safely beyond torment’s reach.

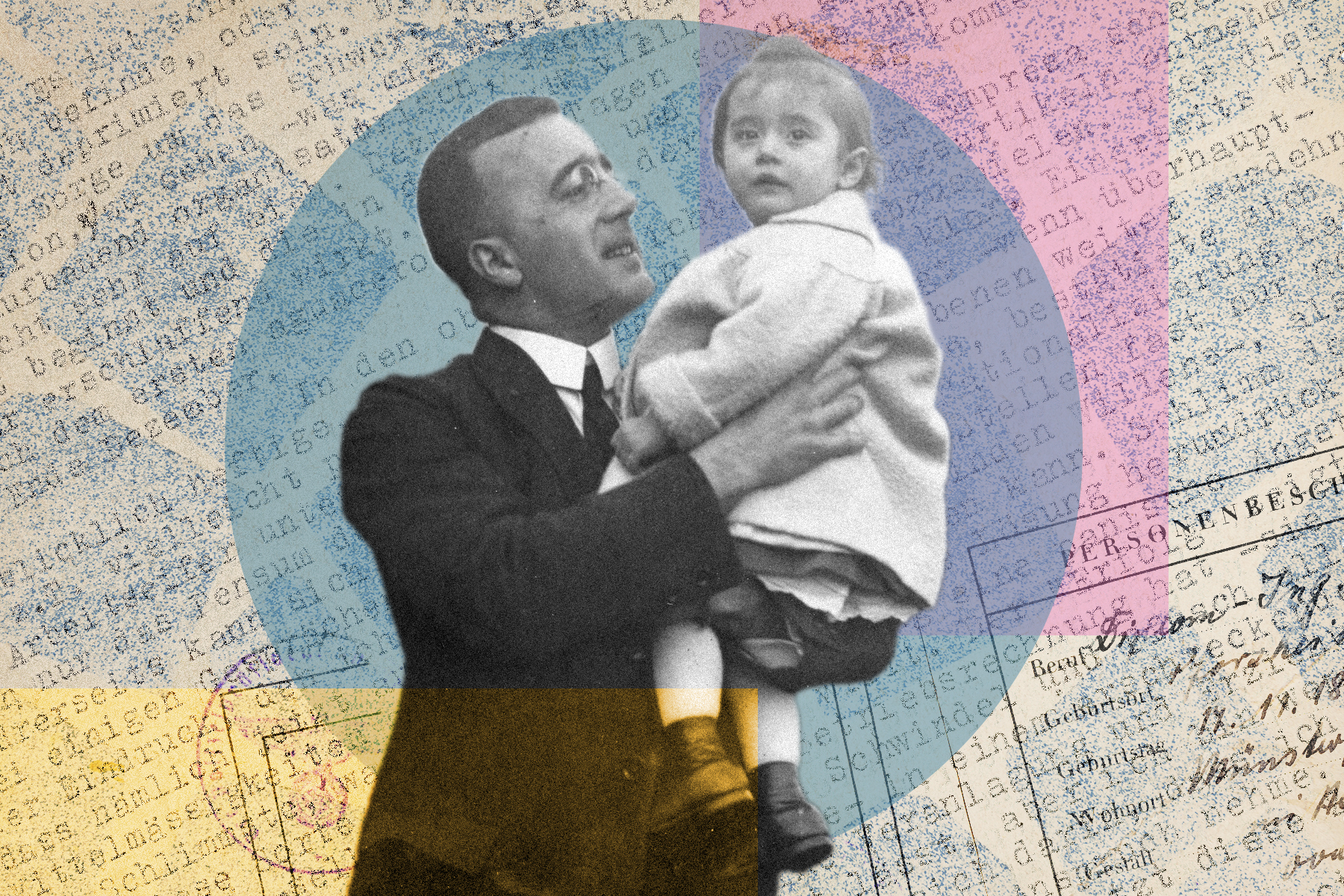

My maternal grandfather, Felix Kuppenheim, died when I was sixteen. I knew he’d fled Nazi Germany just at the onset of the Second World War, ending up in Ecuador, where my grandmother, my aunt, and my mother would join him afterward. I knew this explained why my parents met in Guayaquil and why I was later born in San Tomé, Venezuela. Beyond that, he remained something of a mystery, a quiet, fastidious man who wore grey suits to dinner, with crisp white shirts and a Movado Triple Calendar wristwatch in rose gold.

Of all the many things Felix kept to himself, the one that arguably mattered most was that he was technically Jewish. He was a Lutheran as far as I knew. I wouldn’t have known that my mother’s family on Felix’s side were all Jews, or converted Jews, had an adult neighbour in West Vancouver not needled me on why I’d drawn British insignia on my paper airplanes and not those of the Luftwaffe since my mother and my grandparents were German.

Age six, I thought: fair question. So I asked my mother. Which is how I heard the truth about my maternal ancestry, or at least the barest details allowable back when West Van was a waspy Canadian Kennebunkport where country clubs still barred Jews. I didn’t hear how students attacked my mother and drove her out of school after discovering her Jewish identity. I didn’t hear about her year in hiding on farms near Münster, not knowing if anyone else in her family was even alive. And I certainly didn’t hear about how, fifteen years after the war, Felix would insist on applying for reparations from the German government and receive (for my mother’s entire loss of freedom, her education, her nationality, her childhood dreams) the grand total of $3,500.

All those details would have to wait. I would eventually come to learn that my mother’s family had been a big deal in Pforzheim, Germany, where they lived back then. Felix’s father, Rudolf, was the first OB-GYN in the area and would go on to deliver 19,000 babies. Rudolf’s father, Louis Kuppenheim, had founded a famous silverworks which employed 400 workers and made deco jewellery that still shows up at auctions today. Felix went on to become an engineer before opening a clock wholesaler in Münster. Hans studied physics under Nobel Prize winner Philipp Lenard before taking a job with Siemens. The men of the family all served with distinction as officers in the First World War. They were men of service, business, and science, with Rudolf even converting to Christianity when that seemed the right thing to do, such that Hans and Felix were themselves baptized.

Yet, for whatever mix of personal and practical reasons the family converted, they remained so identifiably part of the Jewish legacy of the Baden region that when historian Christoph Timm published a book called Jewish Life in Pforzheim in 2021, he put Dr. Rudolf Kuppenheim and his sons Hans and Felix right there on the cover.

After settling into my seat on the plane, I find myself examining the cover photo, considering the family that I’m travelling halfway around the world to memorialize. The portrait was shot at Rudolf and his wife Lilly’s flat on Luisenstrasse in Pforzheim, not far from Siloah St. Trudpert Klinikum, the general hospital Rudolf walked to every day for work. I find myself imagining that he would have known every person he passed on the street, many of them from the very moment of their birth.

Yet something darker also lingers in the shadows of the image. Each adult has glanced away from the camera, seemingly aware of themselves and the brittle uncertainty of the moment. It’s 1935. They’ve all read Mein Kampf. They feel something coming.

Rudolf and Lilly would be rounded up for the deportation of Jews from Baden only five years later, in October 1940. And that would have been the end of them—shipped to Gurs, the “limbo of Auschwitz,” along with the other Jewish deportees from the area—had the doctor not opened his door that morning to find himself face to face with a young soldier whom he had himself delivered, whose first breath he’d encouraged, whose face he’d gazed down on before the soldier’s own mother did.

The soldier recognized the doctor, of course. So he left Rudolf and his wife to collect their things. And Rudolf, nearly seventy-five at the time, returned to the living room, where Lilly reportedly sat waiting for him next to his First World War medals and a photograph of the doctor and his sons in uniform. Also, a vial of morphine and a syringe. Rudolf administered the overdose to Lilly first. Then he refilled the syringe and injected another killing dose into his own left forearm.

Their suicide didn’t go unnoticed in Pforzheim, where crowds reportedly attended the funeral, at St. Michael’s Castle Church in the centre of town. But that didn’t mean Hans or Felix could attend. Hans had only just escaped to New York via a transfer from Siemens. And although Felix travelled from Münster to Pforzheim for the funeral, he was apparently warned by a well-intentioned municipal official, who told him to leave immediately lest he be deported himself. So he fled to Ecuador, leaving by rail across Russia. Meanwhile, both men’s wives, and both of Felix’s half-Jewish children, defined as such by the Nuremberg Race Laws, remained behind, Traute with her aunt Ilse in Berlin, Gertrud and Ursula remaining in Münster.

And here we come to another matter, in addition to his Jewish roots, that Felix kept rather importantly to himself, carrying the truth for so long that it became my mother Ursula’s to conceal thereafter. Only with her death in 2006, and later my father’s death in 2016, was it finally delivered to me in full.

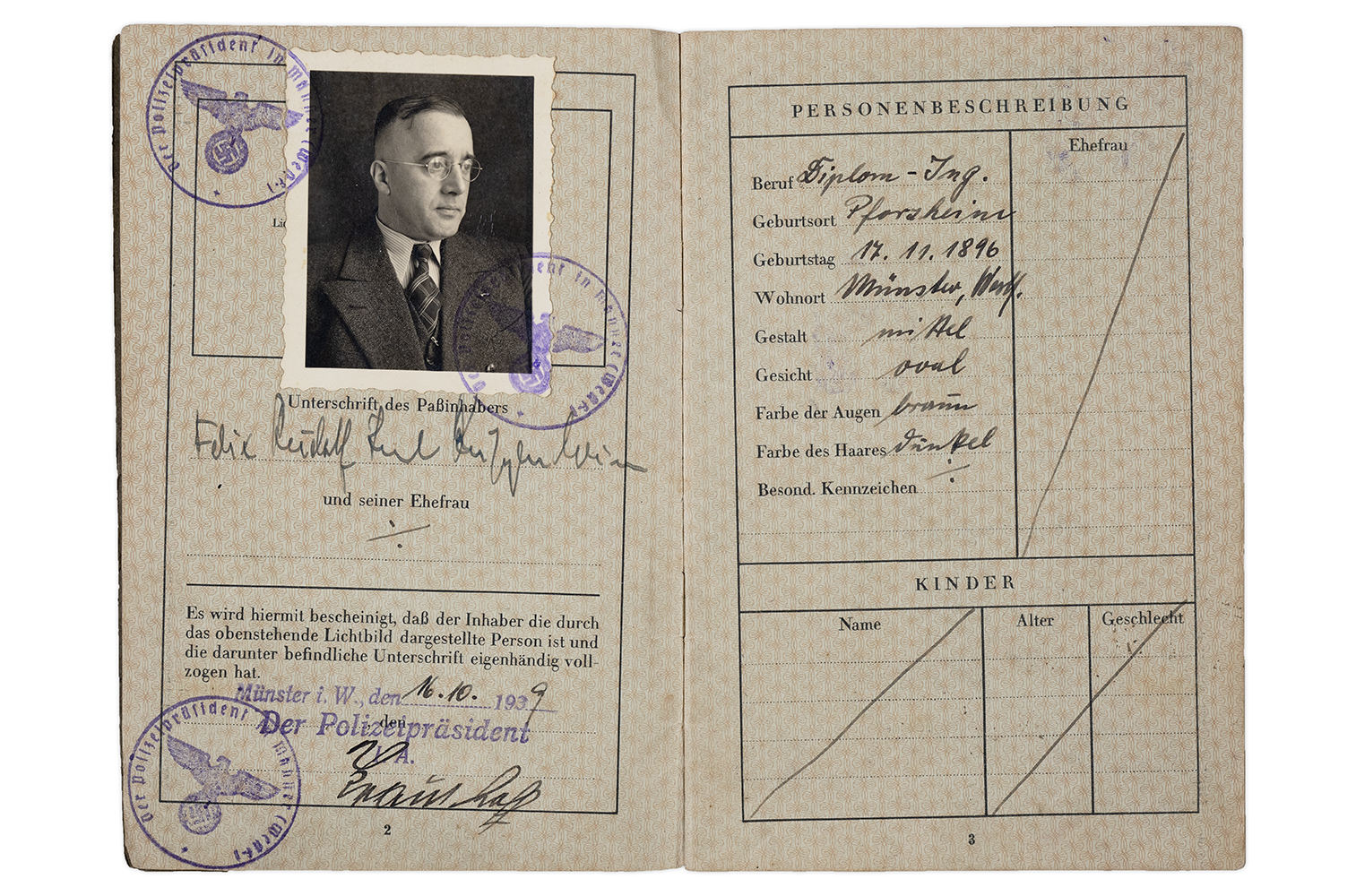

Felix kept receipts. I mean that in the colloquial sense: he documented his family calamity, archiving physical records and evidence. But actual receipts too: meals and hotels, train and boat tickets for Felix’s flight from Germany, through Russia, to Japan, to Panama City, to Guayaquil. Those plus photographs, plus seemingly every scrap of paper ephemera Felix encountered along the way: menus, postcards, passenger lists, itineraries and permits, plus every identification card and passport ever issued to Felix, including the Reisepass he used to escape Nazi terror, stamped with the bright red “J” for “Juden” and his name amended to include the additional middle name “Israel.”

But at the heart of this vast collection are the letters and journals written and exchanged by the two brothers over the eight years of their separation from family: carefully typed, pages numbered, bound in yearly volumes with string. Felix collected 10,000 pages of this material—a rare two-sided correspondence between Holocaust survivors and a stark depiction of the physical and psychological reality of exile.

Near to her final days, my mother told my sister Shelagh, whom I’ll be meeting in Berlin on arrival: “Give Opa’s papers to Timo. He’ll know what to do with them.” So this collection of documents and ephemera finally came to me. And it would be in my living room a year later that the papers would elicit a one-word response from rare manuscript appraiser Stephen Lunsford: “Astonishing.” That is how the Kuppenheim papers were donated to the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre, where they will be digitized, translated, and eventually published in an online archive for use by Holocaust researchers from around the world. And that is how my family’s reunion over the laying of these Stolpersteine memorial stones was finally brought about.

But I take my mother’s directive with regard to these papers to mean something even more: that I should know what to do with the memory of the men who wrote them, the family history to which they attest, the potential reconciliation with Germany that wasn’t possible for any of those involved while still alive, and perhaps most importantly, the revealed legacy of an existential relationship with Jewish identity, whose dimensions I’m only just becoming aware of.

Those are the bigger tasks. And as I stare at that 1935 family photo again, the plane now pivoting to face eastward along the YVR runway, I note that one person has made eye contact with the camera and therefore seems to be staring directly at me. My mother. She’s a child, clueless as I was when I posed to her that crucial question right around the same age: “Are we Jewish?”

She holds my gaze now as then. And she’s trying to convince me across the decades: when the time is right, I’ll know what to do.

Berlin is freezing. I walk the icy streets to the Mühlendamm Bridge and look out along the silver water. It’s Christmas in the city. And there are lights on the Berliner Dom to the north. There’s a Christmas market in Gendarmenmarkt, the smell of Glühwein and pretzels in the air. And to the east, the great Soviet monument of the Berliner Fernsehturm radio tower rises above Alexanderplatz like a glass ornament touching the dirty clouds.

I’m Canadian yet I’m wrapped in three layers, with a wool cap and a scarf around my face. Berliners are cycling by, no hats, no gloves, sailing past the graffitied walls. Here, in the capital of Germany, I find the air bites with conflict after generations of division. The memorials remind you of this, weighted as they are with woeful recollection, though perhaps you feel this more pointedly if your own ancestors were the human sacrifice.

The Kuppenheim cousins trickle into town. It’s a strange and happy gathering, with three languages on the go at all times. Dinner that night is at a tapas restaurant in Spittelmarkt—the only reservation for twenty I can find in all of Berlin—where the clamour of conversation and laughter suggests we’d been taking meals together all our lives.

We eat grilled squid and chorizo. We share stories. Then we wake the next morning to take in Berlin like the history lesson we’ve never had the chance to absorb together, that necessary ritual lost to the generations scattered. So we stumble out on the ice-rutted streets to the Topography of Terror Documentation Centre, where I stand in front of the same images that would have confronted my mother. The sign on the truck reading, in part, only he who works for the Volk community has the right to live. Or the one around the neck of the young Jewish man declaring I have defiled a Christian girl.

At the site of the former Sachsenhausen prison camp, we get a tour from the museum’s deputy director, Astrid Ley. We stand on the frozen field next to one of the prisoner barracks that was half burnt down by neo-Nazis in the 1990s. It’s been rebuilt to house a display of the work prisoners were forced to do here just a few train stops north of the theatres and cafes of Berlin. Above a recessed gallery, we gaze down on the remnants of shredded clothes and leather goods, all confiscated from those sent to Auschwitz and Buchenwald, Bergen-Belsen and the other camps, shipped here to be torn apart in search of valuables that might be hidden in a pant seam or a coat lining, a shoe heel. In Berlin, history falls into a pit at your feet. Or it buries you with its colossal size, its apocalyptic load of soil and sorrow. And on some plane between these experiences, you find the Stolpersteine.

We walk the streets of the Jewish quarter and photograph those we come across. Under an art project begun in 1992 by Berlin-born sculptor Gunter Demnig, the four-inch square brass cobbles are set into the street among the other stones. Each bears the name of a Nazi victim, dead, tormented, or driven away for being Jewish or Roma or homosexual, or disabled, Black, Sinti. There are a hundred thousand Stolpersteine in total on the streets of Europe, though mostly in Germany—individuals and couples, family groupings of three and four—outside of the places where the victims last had peace. I don’t really see them until I suddenly see them. And then every sight line snags on a dull brass plaque at shoe level, a bristling constellation of individual losses, each a tiny glint the size of a personal universe.

I grimace, choke up, stand dumbfounded outside the Adidas or the Moleskine store, the WeWork, the place that sells the expensive pour-over coffee. I count the names: the Davidsohns, the Bukofzers, the Schneebaums. I see you, Gottfried and Lotty Hollander, deported to Auschwitz in 1943. I stand with you off Oranienburgstrasse behind the New Synagogue, where the tour guide is an American who considers the group of us, asks if we’re Jewish, then listens politely to the gabbled and stammering response.

I think: part Jewish, part Christian, part secular, part irreligious, part muddled, and part certain yet somehow also now wrapped into a greater body of belief and doubt and residual wonder. And as we approach the synagogue’s security gates, past the metal detector, the bomb-proof doors where they’re running everyone’s bags through an X-ray machine, I catch our tour guide’s glance again and shrug. I want to answer his earlier question by saying: Yes. No. It’s complicated.

I’ll think of this exchange that evening as we gather in Frohnau, a northern neighbourhood of Berlin. We’re here to lay the first three of the Stolpersteine, those for Hans, Ilse, and Traute. But I’m numb from the cold and from not knowing at all what to feel—these people swirling under the bright-yellow construction light as the brass plaques are lowered into the cobblestone walk, the cement trowelled into place around them. A crowd has gathered, fifty or more—members of the local Stolpersteine committee and their friends, and the people who live in the nearby houses. The mayor speaks. These horrible things that we did to you, she says. We lost you. And you returning to us is our gift.

I’m struck by the word gift coming from a politician who didn’t really have to show up on this freezing night in the first place. A trombone plays a mournful tune from across the way while the police watch carefully and the crowd sways slowly in place. Then I see it: we are the gift to the ceremony, and this ceremony is, in significant part, for them.

Later, I jolt awake in my hotel room and swing my legs out of bed, sit there for many seconds, suspended in the grainy light, registering the pixelated surface of things, the grey tones, the sandy edge of a doorway and a hall. I’m thinking of Sachsenhausen, the frozen field, the half-burnt barracks, the display of personal belongings. And I’m remembering a story Ley told us about a group of starving prisoners left locked in the infirmary by the guards when they fled the approaching Russians in the spring of 1945. And after several hours, when the Russians had still not appeared, those last survivors broke out of the infirmary to forage for food, scrabbling in the dirt of the workshops with their hands, one of them digging up a milk bottle full of diamonds.

I imagine the bottle held up in the grey light, the sickened amazement the prisoners must have felt, the glittering shards of light captured there, a king’s ransom stolen from the innocent, the sun’s rays aching as they passed through the cuts and panes of the faceted stones.

The escaped prisoners didn’t keep what they’d found. And they didn’t leave the precious stones for the Germans or Russians to find later. The starving men took the milk bottle south of the camp instead, to the shores of Lake Lehnitzee, free of ice but very cold. And with a boat they found, they rowed the milk bottle out into the middle of that lake and emptied it into the black waters, let the diamonds sink into the deep, to the bottom, to the mud, beyond all reach.

I see Hans in New York City, his head cocked as if hearing that trombone, as if seeing those diamonds glittering in the failing light. I see his dwindling form now under the elevated tracks, newspaper in hand. He is sifting into the very pixels, spreading into the light of America.

Then he’s gone.

On the train to Münster, four hours west of Berlin, in North Rhine–Westphalia, I go through the Kuppenheim family photos I’ve brought with me, prepping for the family history presentation I’m giving the evening after we lay the second set of Stolpersteine, those for Felix, Gertrud, and my mother, Ursula.

The stones will be laid in Friedrichstrasse, near the railway station, where my mother’s family lived and where Felix ran his watch and clock wholesaler. My mother remembered the whir and tick of mechanical movements in the front room when she came home from school. Of course, there’s a new building there now. The old house was destroyed, like much of central Münster, in the air raids of 1943 and 1944. I have a picture of the bombed-out house. And as I look at it now, I imagine thousands of shattered watch and clock components in the rubble, tiny screws and levers strewn in the dust, minute wheels and mainsprings scattered among the bricks and beams and broken glass.

I’m nervous about the presentation—which is irrational, as the people who attend will be highly sympathetic. The event is scheduled at the Villa ten Hompel, a museum to Nazi war crimes, in Münster. But maybe that’s the source of the nervy feeling, knowing that Villa ten Hompel itself was once the regional head-quarters of the infamous Ordnungs-polizei, the “Order Police,” the same uniformed regiments that carried out the Nazis’ early racial extermination programs in the east, burning Jews in their synagogues or shooting them into ditches, then drinking themselves into a stupor every evening so they could go out the next day and do it all over again. My mother spent a year in hiding after getting thrown out of school, because people exactly like those in the Ordnungspolizei wanted her dead. Were she alive today, would she have even set foot in the building, knowing who’d once hung their peak caps and polished their jackboots here?

I’ve been working on a podcast about the archive and the stories it contains. My producer, Anthony Cantor, joins me for breakfast in the dining car: cheese and salami and coffee and a single order of bread that turns out to be three enormous pretzel rolls. Cantor is more chill about the presentation than I am, pointing out that I’m well prepared, with my Kuppenheim family photographs laminated and laid out for presentation.

“Germans are big on laminated things,” he says, speaking to the national love of organized documentation. “Also binders. No house here is complete without a wall of binders with receipts and bills going back to 1973.”

Cantor is Jewish and born American though a long-time Torontonian by now. A history PhD by training, he speaks perfect German and is a deep expert on the country and its history, via education and marriage. His quip about the paperwork speaks to why we’re here—our project to discover what’s in the archive—and illuminate what happened to the Kuppenheims, following on with perfect logic from Felix’s methodical collection of that 10,000-page proof of persecution and exile.

I leaf through the images, noting how expressions migrate with the year of the photo. Felix in a family picture from 1934 is beaming. By the time of his Reisepass, he looks grimly determined. Two years into exile, posing in a rumpled white linen suit with colleagues, next to a locomotive in the trainyards where he worked in Quito, I can see the deep fatigue, his face darkened and haunted.

Pictures of my mother show the same progression. The kid posing with her rucksack on the first day of school is the girl who wanted to be a doctor like her famous grandfather Rudolf. A decade later, she’s sixteen and looks utterly battered, her face that of the young woman exposed at school for being half-Jewish, attacked, humiliated, cast out, gone into hiding, lucky to be alive. Her bruised expression carries the weight of every day she’s spent alone. But it’s also the face of the woman she would become as a result, who would meet my father in Guayaquil, have five kids and raise them in Venezuela, emigrate to Canada, to Vancouver, where she’d break down sobbing in the family Volvo at the sight of searchlights over the Pacific National Exhibition, as we drove down Hastings Street, all of us kids watching wide eyed from the back seat as my father tried to comfort her.

Seeing all this in her face, her past and her future, I swivel my head to the window, to the landscape sweeping by as we draw near to Münster. Along the perimeter of the fields here, there are stripped trees, shivering in the frigid cold, dark orbs suspended in the branches of each. These are birds’ nests, I see. Empty now, bundles of twigs against a frozen sky.

Arriving from Berlin, city of somber memorials, I find the Münster old town to be as pretty as a picture book, with its winding cobblestones and half-timbered buildings. We tour the city centre with Peter Schilling, chair of the local Stolpersteine committee, with whom I’ve been corresponding for over a year to get these last three stones approved. Münster is famous for being bike friendly, for a sculpture festival that populates the city squares with art, also for a college-town feel due to the local university. It’s easy to imagine a blissful childhood in this place, particularly during the holiday season, with snowflakes and the smell of baked goods in the air, the trees all hung with lights, and a trickle of classical music to be heard wherever you roam.

We walk past the shops, around the treed promenade, along the banks of the winding Münstersche Aa river. I gaze up in wonder, as my mother once did, at the towering St. Christopher statue in the nave of St. Paul’s Cathedral in Domplatz, or at the astronomical clock found in the hallway around the back of the sanctuary. A fantastic thing, this clock. I’m like a kid myself in front of it, waiting for the figurines perched high on the corners to move with the marking of the hour: the trumpeter and woman with the bell, the skeleton of death standing next to old man Chronos, who turns an hourglass in his hands. Felix would surely have explained the device to little Ursula at some point, how the clock’s face is an enormous astrolabe showing the phases of the moon and the location of the planets, or how the perpetual calendar provides dates from 1540 through 2071, a Dionysian era of 532 years.

The clock here isn’t the original. It was completed in 1542 to replace the one the Anabaptists had destroyed during the Münster Rebellion eight years prior, at the end of which the rebel leaders were executed in Prinzipalmarkt, just a block over, their bodies hoisted in three metal cages to hang on the steeple of St. Lamberti church for all to view. The cages were knocked off the building by an Allied bomb during the war, only to be replaced during reconstruction. But in her oral history, my mother describes hating the cages for the cruelty they represented and averting her eyes as she walked this route to school.

She’d likely grown sensitive to cruelty by then. Young Ursula was only three years old when the Reichstag burned, five by the time of the racist Nuremberg laws, six when Italian fascist leaders were being toured around the Sachsen-hausen prison camp as if it were a satellite attraction to the Berlin Olympics. She was eight years old on Kristallnacht when she smelled the synagogue burning from her own bedroom window, and later when the police in this idyllic snow globe of a town were allegedly so overwhelmed by people denouncing their neighbours for being Jewish (even when they weren’t) that the cops had to shut down their own snitch lines.

But the most savage predicament was yet to come. The year Ursula’s beloved grandparents killed themselves to escape deportation was right after membership became mandatory for girls of her age in the Band of German Maidens, or BDM, the Hitler Youth for girls from which my mother was racially barred. A few years later, the BDM would be in charge of Ursula’s adolescent life entirely, when its members, and those of the Hitler Youth, were tasked with leading troops of adolescent school kids, evacuated from urban centres, into the countryside to avoid the bombing.

Now here was a trap of diabolical design. By law, Ursula shouldn’t have been in high school at all by this point in the war. The so-called Mischlinge were banned from public education beyond middle school in 1942. By 1943, a kid only had to be outed as half-Jewish (or any part gay, Roma, or disabled) to potentially be sent to one of the euthanasia centres like Hadamar, a four-hour train ride south of Münster, where non-Aryan children who were ill or deemed “useless eaters” were indeed murdered as part of the Nazi program to clear up German hospital beds for soldiers. Gertrud somehow managed to keep her daughter enrolled in school, avoiding these clearly worst-case outcomes, only to have a now thirteen-year-old Ursula get sucked up into the Kinderlandverschickung program, where she’d be isolated in the countryside under the direct supervision of other kids who wore swastikas on their sleeves.

My mother ended up in the Bavarian town of Reit im Winkl, staying at a guest house called the Feichtenhof. I have to assume that Gertrud thought this was, on balance, a safer place than Münster or perhaps she would have arranged for her daughter to go into hiding earlier. In her oral history, my mother remembers that her denunciation ultimately came from Münster, from the mother of a classmate who lived near Friedrichstrasse and was aware that Felix had left the country. We don’t know the names here. But if the mother had reasons to denounce young Ursula, her daughter clearly had her own reasons for what came next. She and her friends put needles in Ursula’s bed which cut her until she bled. And there would have been more if a staff member hadn’t taken my mother out of the dorm for her own protection, then called Gertrud to come get her daughter to safety.

We tour the countryside where my mother went into hiding after her return from Reit im Winkl. Schilling meets us again in the town of Telgte. He tells us that, before our arrival in Germany, he ran an advertisement looking for information about my mother’s time in that area, with a photograph of Ursula as a teenager. Do you know this girl? Do you know where Ursula Kuppenheim stayed near Telgte in 1944? The ad didn’t get a single response.

Schilling shows us around, taking us to the Provost Church of St. Clemens chapel, where my mother remembered sitting on her visits into the town. I take the back pew and feel winter penetrate the walls, the seats, my clothes. I light a candle for her, sign the guest book. Then we walk outside, past pastry shops and furniture stores, art galleries and a real estate agency with pictures in the window suggesting prices in line with Point Grey, Forest Hill, Park Slope.

We drive the country roads, five of us now crammed into a car. It feels pointless, cruising the byways, staring out over the green fields to the red-roofed houses under the trees. My mother might have stayed on this farm here digging potatoes, or across the way helping with the flax harvest. But in the end, our looking and our lostness becomes the entire point. We scan these fields and don’t find her. And that much leaves the landscape exactly as it would have been for her: empty of comfort, with no trace of the familiar, no trace of her own mother.

We make our way back into Münster. And in the afternoon, we walk from our hotel in Bahnhofstrasse—which Schilling informs me was called Adolf Hitler Strasse during the war—up into the small street where Felix and Gertrud and Ursula once lived. It’s busy here. There are buses and cars streaming by. Schilling is there with local historian Adalbert Hoffmann. And a small crowd has gathered to watch as the stones go into the ground. A young man who lives in the new building at that address comes out to ask polite questions and to stand respectfully with us. The polished stones are lowered into place, the brass gleaming. Someone has brought white roses, and these are laid out on the sidewalk one by one.

I say a few words. I can’t remember any of them. The press interview me and my siblings as a man brushes rudely past, wearing a suit, pushing a bicycle. He is red faced and angry. He calls back: These sidewalks are for ordinary Germans!

My cousin Silvia answers for all of us, effortlessly, perfectly: But this is not an ordinary moment.

At which point, the traffic surges again, Münster growls low in the background, the night is on us, and the chill is once again descending.

My talk at the Villa ten Hompel goes fine. I needn’t have worried about crowd response. More about myself. In the green room before going on stage, I inspect a photo of the villa from the ’30s, noting the pristine condition of the building and the grounds. The hedges perfectly trimmed. There’s a wide rectangular reflecting pool in the middle of a manicured lawn.

Those Ordnungspolizei had pretty nice digs, I observe to Hoffman, who then explains to me that even after the police units were disbanded, many of the same people continued to work in the villa. Some served on the denazification committee that was housed here, ostensibly designed to clear out former Nazis but which often did not. Others went on even after that to serve with the reparations department, also head-quartered at the villa, tasked with assessing compensation claims from those whom the Nazi regime had tried to destroy.

So that’s how I learn—minutes before heading out to give my talk about Kuppenheim history—that it was in this very building that some former Nazi, quite possibly a former member of the Ordnungspolizei itself, had likely been the one to decide that amends for my mother’s whole life amounted to a few thousand dollars.

I present the biography with my Swiss cousin Caroline, in English and then German. I hold up my laminated photographs. And I find myself trying to suppress two contradictory and disturbing feelings. On the one hand, I worry that I might be getting angry. I sense my voice rising, as if I’m trying to drill the story home. No matter that all these people are here willingly, interested in the truth. A part of me is struggling not to feel that they must still be punished.

On the other hand, and making no sense whatsoever, part of me is wondering if I should be there at all, since my family survived. Descend into the madness of atrocity long enough and you may start to think that sufferings can be compared and measured, one weighted against the other. I’m feeling that.

I relate these thoughts to Cantor after the presentation. He’s recorded it. He’s also been serving as an emcee of sorts, as Schilling and everyone present have by then figured out his German is perfect. He listens to me characterize my odd combination of anger and victim imposter syndrome. Then he says it quite simply: “Your mother knocks on one wrong door for the better part of five years and none of you even exists.”

We head south in the morning, two final stops to make on this journey, which I see now is going to be just the first of many. The Kuppenheim papers are now safe at the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre. But so much remains to be done: digitization, translation, not to mention me reading and processing what this archive actually holds. And in the car now, heading south, the landscape once again spilling past, it’s the fragility of progress that strikes me. The tentative nature of all first steps.

We stop in Pforzheim first, to visit the Stolpersteine of Rudolf and Lilly, whose deaths launched the heart of these matters for the Kuppenheim family. Their two cobblestones are found on Luisenstrasse, where they used to live. It’s a car park now. And there’s a red door here that appears to lead back to a night club of some kind. But once, this was the seat of the family. And some number of floors above us was the living room where that 1935 photograph was taken, where my mother stared directly into the camera and the future. The same room where Rudolf and Lilly would take their own lives. The brass plaques on the sidewalk in front of us are sadly tarnished.

We move to the cemetery next, where the Kuppenheim grave site is found. Rudolf, Lilly, their sons Hans and Felix, Gertrud and Ilse as well. The elders are all together now in the mossy green under the hanging trees. It’s raining steadily. A film crew from the local paper has attended. I answer questions, but I’m thinking instead of what remains. We’ll digitize and translate Felix’s 10,000 pages, make them available to Holocaust researchers around the world, sharing their rare, even “astonishing,” insight into exile and the legacy of loss. Cantor and I will make our podcast. Now that the Stolpersteine shine in their places, these names written back on the surface of the town from where they were once very nearly erased, we’ll share the stories the archive reveals—the men and women it has contained in silence for all these years. Will there be reconciliation in this? My cousin Carlos has received his German passport already. So there is another beginning. And as Ecuador’s own troubles steepen, I’m grateful for that. Let Germany be someone’s place of safety now.

For me, I’ll think of new connections instead, some new tissue growing now between me and a legacy lost. I recall my mother writing from Guayaquil in 1950.

The nights are kind of hard, especially now in the winter, which is the rainy season. The night has a breath of its own—humid and heavy, full of tantalizing smells being hard on the human soul. It makes you homesick and melancholy and hinders sleep . . . In such hours you try to reconcile the past and the present, the past without the sting of bitterness or the unrealistic light of remembering, the present without the struggle for every day life. What is happening in me is the formation of my true humanity. Through millennia of culture and nonculture shines the noble human face marked by suffering. As I seek it, I am actually seeking the face of modern man evolving in me.

Then we wind the car southward still. Up a valley that grows white with snow. And soon we are in Reit im Winkl, where the train stopped and the schoolgirls disembarked. Where the sky domed above them, the sun was bright, and my mother’s life turned toward its darkest moments. I go into St. Pankratius Parish Church, at the top of the main square. And when the church bells ring on the hour, they sound like the music of a great cathedral to me, peals upon peals, call changes and cascades, a kaleidoscope of harmonics and after tones. I think of the Ein deutsches Requiem just then, the torment that shall no longer touch them. I’m weeping in a church, thinking of one young girl, who is my mother, but to whose memory I have now somehow become reborn as a parent.

Muriel Rukeyser writes in her poem “Letter to the Front”:

To be a Jew in the twentieth century

Is to be offered a gift [. . .] The gift is torment.

I’ll take the gift. I’ll hold it close and open it over time. And only later—after coffee and pastry, moderately restored—we’ll drive out toward the hamlet of Blindau together. We’ll knock on the door of the Feichtenhof where my mother stayed, where the other students turned on her and drove her out. No one will answer. And after we speak to a neighbour, explaining why we’re there, he’ll go inside and lock the door behind him.

The Hidden Holocaust Papers: Survival.Exile.Return., a podcast based on this story, can be found here.