Clarity is power: The Trump administration needs a new US Navy Navigation Plan

We are operationalizing our

“Get Real, Get Better” mindset.

—Vice Admiral Brendan McLane, US Navy, as quoted in Seapower Magazine, January 16, 2025

During his Naval Postgraduate School speech in May 2022, Admiral William K. Lescher, vice chief of naval operations, explained the Navy’s new “Get Real, Get Better” initiative, which had been announced in the July 2022 Navigation Plan (NAVPLAN). He stated: “We have to self-assess and be our own toughest critics. We need to be honest about our abilities and be fully transparent about our performance. Once we ‘embrace the red,’ we will be able to identify solutions and more realistically predict our mission readiness.”1“Vice Chief of Naval Operations Talks ‘Get Real, Get Better’ During Latest SGL at NPS,” News Stories, US Navy Press Office, May 24, 2022, https://www.navy.mil/Press-Office/News-Stories/Article/3041666/vice-chief-of-naval-operations-talks-get-real-get-better-during-latest-sgl-at-n/.

The “Get Real, Get Better” mandate must apply to all levels of the Navy including at the strategic level. This Atlantic Council Issue Brief does exactly what Lescher called the Navy to do by critically assessing the Navy’s 2024 overarching strategic planning document: the 2024 Navigation Plan.2Lisa Marie Franchetti, Admiral, US Navy, Chief of Naval Operations Navigation Plan for America’s Warfighting Navy 2024, US Navy, September 2024; Admiral Franchetti was chief of naval operations until February 21, 2025. This evaluation embraces the red by identifying course corrections and the need for greater clarity, specificity, and transparency in its guidance.

The short life of the Navy’s 2024 NAVPLAN

Tactical mistakes may kill you today, while operational error may prove fatal in days or perhaps weeks. A[n] error in … strategy may take years to reveal itself in its full horror.

—Colin S. Gray, “Why Is Strategy Different,” Infinity Journal

Admiral Lisa M. Franchetti, the thirty-third chief of naval operations (CNO), published the Navigation Plan for America’s Warfighting Navy 2024 (NAVPLAN) on September 18, 2024.3“Chief of Naval Operations Releases Navigation Plan for America’s Warfighting Navy,” Public Affairs, US Navy, September 18, 2024. This NAVPLAN is already outdated, no longer applicable, and requires replacement.

The inauguration of President Donald J. Trump on January 20, 2025, voided the 2024 NAVPLAN. Trump wants a bigger Navy by building more ships and has congressional majorities to back-up his policies, while the Navy in its NAVPLAN ranks a bigger Navy—what the Navy calls capacity—as its lowest priority. Indeed, the 2024 NAVPLAN clearly states the Navy “will continue to prioritize readiness, capability, and capacity in that order.”4Franchetti, CNO Navigation Plan, 12. The twenty-eight-page NAVPLAN devotes a few sentences to express the need for a larger Navy, indicating, however, that it will not happen for over a generation because of insufficient funding and an inadequate industrial base.

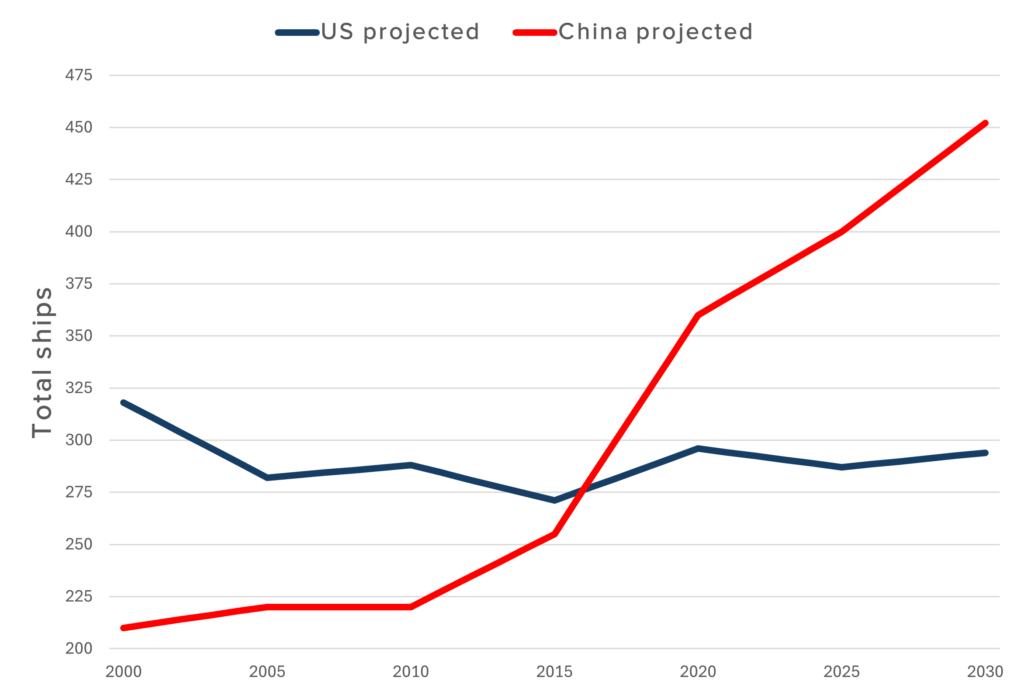

During an interview on the January 6, 2025, “Hugh Hewitt Show,” Trump announced his policy to build more ships for the US Navy. He noted that the United States is “sitting back watching” as China rapidly expands its navy, opining that the United States has “suffered tremendously.”5Hugh Hewitt, “President-elect Donald Trump on ‘One, Big, Beautiful Bill,’ ” Transcript, The Hugh Hewitt Show, January 6, 2025. (Figure 1 displays the trend lines for the size of these two navies.) He said his administration will announce “some things that are going to be very good having to do with the Navy. We need ships. We have to get ships.”6Hewitt, “President-elect Donald Trump on ‘One, Big, Beautiful Bill.’ ” At his January 14, 2025, Senate confirmation hearing, Peter Hegseth, now secretary of defense, echoed that guidance: “President Trump has said definitively to me and publicly that shipbuilding will be one of his absolute top priorities of this administration. We need to reinvigorate our defense industrial base in this country to include our shipbuilding capacity.7To Conduct a Confirmation Hearing on the Expected Nomination of Mr. Peter B. Hegseth to Be Secretary of Defense.” Hearing before the Committee on Armed Services, United States Senate, 118th Congress, January 14, 2025. https://www.armed-services.senate.gov/hearings/to-conduct-a-confirmation-hearing-on-the-expected-nomination-of-mr-peter-b-hegseth-to-be-secretary-of-defense. In addition, Hegseth (in a response to a policy question in this confirmation process) penned that, “Shipbuilding is an urgent national security priority. If confirmed, I will immediately direct the Secretary of the Navy and the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment to create a shipbuilding roadmap to increase our capacity.”8Senate Armed Services Committee, “Advance Policy Questions for Peter “Pete” B. Hegseth Nominee to Serve as Secretary of Defense,” January 6, 2025; see also Ashley Roque and Valerie Insinna, “What Pete Hegseth’s Hearing Tells Us About Trump’s Plans for the Pentagon,” Breaking Defense, January 14, 2025.

In his March 4th joint address to Congress, Trump followed through on his January comments made on the “Hugh Hewitt Show.” He announced his plan to revive US naval and commercial shipbuilding by establishing a White House Office of Shipbuilding. With the exception of its purpose—“To boost our defense industrial base” in order to “make [ships] very fast, very soon”—details on how this office would function remain scarce. Regardless, Trump signaled that shipbuilding is a key theme of his administration and a component of his plan to build “the most powerful military of the future.”9Valerie Insinna, “Trump Announces New White House Shipbuilding Office,” Breaking Defense, March 04, 2025.

Figure 1: US and Chinese naval force levels: Actual and projected (2000 to 2030)

Overview of the Navy’s NAVPLAN

Politicians bear the heaviest blame for a fleet that is 50 ships too small, but the CNO should be explaining the strategic risks and lighting a fire for the funding to arrest the trend.

—Wall Street Journal, February 23, 2025.10Editorial Board, “Trump Sweeps Out Biden’s Officers,” Wall Street Journal, February 23, 2025

NAVPLANs are a series of planning documents that convey the Navy’s most important policies for implementation above all other Navy guidance documents, including the tri-service, unclassified strategies, such as the 2007 A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower,11James T. Conway, Gary Roughead, and Thad W. Allen, “A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower,” Naval War College Review, October 2007. the 2015 revision of A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower,12Joseph F. Dunford, Jr., Jonathan W. Greenert, and Paul F. Zukunft, A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower: Forward, Engaged, Ready, March 2015, https://news.usni.org/2015/03/13/document-u-s-cooperative-strategy-for-21st-century-seapower-2015-revision. and the 2020 Advantage at Sea.13David H. Berger, Michael M. Gilday, and Karl L. Schultz, “Advantage at Sea Prevailing with Integrated All-Domain Naval Power, December 2020. Each CNO personally authors an unclassified strategic plan—a NAVPLAN—to outline a path for the Navy’s forward progress during their four-year tenure. Modern NAVPLANs have four purposes: explain how the Navy, as part of the Joint Force, intends to deter and defeat threats to US national security; guide prioritizing and rationalizing Navy plans and programs; provide a persuasive framework for Navy funding requests; and source strategic communications to deter threats and reassure allies and partners.14Derived from Ronald O’Rourke, “The Maritime Strategy and the Next Decade,” US Naval Institute Proceedings 114/4/1,022 (April 1988).

Crafted ostensibly for an internal Navy audience, these NAVPLANs identify the “biggest challenges to [the Navy’s] forward progress” and provide a “coherent approach to overcoming them.”15Richard P. Rumelt, Good Strategy/Bad Strategy: The Difference and Why It Matters (New York: Crown Publishing Group, Random House, 2011), 2. NAVPLANs also have three other audiences: allies and partners, as well as potential adversaries; key decision-makers in the executive and legislative branches of the US government; and national security thought leaders in the public domain (e.g., think tanks, academia, news media, and industry). As discussed below, the latter two audiences are critically important to the Navy. The American public, however, is not a primary audience because its interests typically lag behind emerging security issues.

The 2024 NAVPLAN: Recognize the good

The 2024 NAVPLAN is a remarkable document with three instances of notable clarity. First, the NAVPLAN unequivocally declares a strategic end to achieve “readiness for the possibility of war with the People’s Republic of China by 2027.”16Franchetti, CNO Navigation Plan, III. By specifying China as a primary threat and with a select year for potential conflict, the NAVPLAN provides focus and clarity of purpose. The NAVPLAN zeroes in on China and describes seven priority areas to improve Navy readiness. This is a positive, clear expression of the ranking that past documents lacked. Second, the 2024 NAVPLAN cites and supports former CNO Michael Gilday’s 2022 guidance by calling for 3 percent to 5 percent “sustained budget growth above actual inflation [to] simultaneously modernize and grow the capacity of our Fleet.”17Franchetti, CNO Navigation Plan, 12. The NAVPLAN warns, “Without substantial growth in Navy resourcing now, we will eventually face deep strategic constraints on our ability to simultaneously address day-to-day crises while also modernizing the Fleet to enhance readiness for war both today and in the future.”18Franchetti, CNO Navigation Plan, 12. Last, this document devotes an entire page correctly highlighting how unmanned ships and aircraft technologies are the “changing character of war,”19Carl von Clausewitz, On War, eds. and trans. Michael Howard and Peter Paret (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1984), 85. According to Clausewitz, the character of war refers to “the means by which war has to be fought.” These means are constantly changing as technology has a significant influence, as do doctrine and military organization. Changes in the character of warfare may occur slowly over generations—evolutionary—or quite rapidly—revolutionary. These changes affect the tactics of employing capabilities and influence the development of strategy. by “pushing asymmetric capability, at lower cost, to state and non-state actors alike.”20Franchetti, CNO Navigation Plan, 9. In response, the NAVPLAN focuses the Navy to operationalize “robotic and autonomous systems,” 21Franchetti, CNO Navigation Plan, 12.commonly known as drones. 22The 2024 NAVPLAN has seven high-priority “targets” or subobjectives, personally approved by the CNO. The second target listed on page III is to “scale robotic and autonomous systems to integrate more platforms at speed.” This clarity of expression is admirable.

The 2024 NAVPLAN: Embrace the red

In a world deluged by irrelevant information, clarity is power.

—Yuval Noah Harari, 21 Lessons for the 21st Century

As mentioned, this issue brief is a critical assessment in the spirit of “Get Real, Get Better.” The 2024 NAVPLAN has major deficiencies that require correction in the next NAVPLAN. Overall, the current NAVPLAN projects an aspirational tone, with its lack of explicit strategic assumptions, risk assessments, and descriptions of the “why” and “how” of achieving its objectives. Specifically, it lacks:

- Focus on the Navy’s two most important audiences

- Clarity and specificity

- Guidance on consequential issues

- Frankness

- A serious format for a serious document

1. Lack of focus on the Navy’s two most important audiences

The NAVPLAN’s two most critically important audiences have a learned membership, making them substantially different from the American public. They are the key decision-makers in the executive and legislative branches of the US government, and national security thought leaders in the public domain (e.g., think tanks, academia, news media, and industry). The NAVPLAN is the Navy’s only unclassified document to inform these two influential audiences, whose decisions and activities control in large part the funding for the Navy’s force structure, capabilities, and personnel requirements. Indeed, this is why Navy senior leaders make the rounds to Washington think tanks, security forums, and the war colleges and interact with news media to explain the NAVPLAN’s guidance. For this reason—garnering support and advocacy for the Navy’s budget—the information requirements of these two principal audiences eclipse the needs of the other audiences.

In contrast, the American public is a secondary audience because it is a reactive rather than a proactive audience. Most Americans are not reading and reflecting on the nation’s current global security challenges and the need to rearm. Instead, the American public responds to events usually after seeing graphic, tangible evidence. For example, viewing disturbing images of dead American military personnel and destroyed US aircraft during the April 1980 Operation Eagle Claw, a flawed mission that helped to elect Ronald Reagan and generated enormous public support for his defense buildup.

2. Lack of clarity and specificity

We must communicate with precision and consistency, based on a common focus and a unified message.

—General David H. Berger, US Marine Corps, Commandant’s Planning Guidance

The 2024 NAVPLAN has numerous instances of inadequate clarity and specificity. For example, the NAVPLAN directs the Navy to increase its readiness for a possible conflict with China by 2027. The Navy, however, must convey more than readiness for a global war with China. It must also unequivocally transmit that the Navy will deny China their preferred kind of war, destroy23The NAVPLAN should follow the example of General Colin Powell, US Army, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, with unambiguous clarity. He famously stated at a Pentagon press briefing on January 23, 1991, announcing the US Gulf War plan against Saddam Hussein’s army, saying: “Our strategy in going after this army is very simple. First, we are going to cut it off, and then we are going to kill it.” See Eliot Brenner, “Powell: ‘We’re Going to Cut It Off . . . Kill It,’ ” UPI, January 23, 1991. the Chinese navy, and terminate the war on terms favorable to the United States.24The author based these three objectives on the Navy’s famous 1980s Maritime Strategy. James D. Watkins, “The Maritime Strategy,” US Naval Institute Proceedings 112/1/995 Supplement, The Maritime Strategy, January 1986.Beijing must feel the force of President Reagan’s famous words: “You lose; we win.”25Henry R. Nau, “We Win, They Lose—Ronald Reagan Armed with the Intent to Negotiate,” Claremont Review of Books, Book Reviews, Winter 2022/23. The US Navy needs to signal the unquestionable destruction and defeat of Chinese maritime forces. This unabashed expression of lethality was a great strength of the 1980s Maritime Strategy. Moreover, the Navy’s allies and partners must comprehend that the Navy is fully committed and prepared for a potential war with China.

The NAVPLAN omits explanations about why and how the Navy achieves its objectives. Without this explanation and context, the NAVPLAN’s statements are no more than assertions. For example, the document states, “We establish deterrence and prevail in war when we work as part of a Joint and Combined force.”26Franchetti, CNO Navigation Plan, 13. There are no further particulars about how the Navy intends to deter and win in a war. This guidance—or rather this assertion—implies that the Navy uses the same approach regardless of who is the enemy. Obviously, the differences between a war with China or Russia are profound, and the Navy’s approaches to deter and win are different. For starters, each adversary has entirely different strategic objectives. Moreover, a war with China occurs in a predominantly maritime theater with few US allies, whereas as a war with Russia occurs in a predominantly continental theater with an effective NATO security alliance. The differences continue, demanding greater specificity than the NAVPLAN’s abstract and broad statements that provide little useful guidance, especially given the ominous, if not dire, warnings by the Commission on the National Defense Strategy.27Rep. Jane Harman and Amb Eric Edelman, Chair and Vice Chair, Commission on the National Defense Strategy Report, July 2024, v. The commission report said: “The threats the United States faces are the most serious and most challenging the nation has encountered since 1945 and include the potential for near-term major war. The United States last fought a global conflict during World War II, which ended nearly 80 years ago.” This lack of specificity becomes more disturbing in light of the NAVPLAN’s clarion call to prepare for a possible conflict with China in 2027. It is a confounding disconnect.

To paraphrase Dr. Samuel P. Huntington, the eminent American political scientist and author of The Soldier and the State and Clash of Civilizations,28Samuel P. Huntington, “National Policy and the Transoceanic Navy,” US Naval Institute Proceedings 80, no. 5, May 1954. the Navy’s two principal audiences cannot support the Navy’s requests for funding without pertinent information. As Huntington expounded, they need to know how, when, and where the Navy expects to protect the nation against military threats, such as those now posed by China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea.

Furthermore, the 2024 NAVPLAN misses another opportunity to communicate the Navy’s relevance to a war with China by not expounding on the implications of a war in a predominantly maritime theater with few US allies. George Friedman, an internationally recognized geopolitical forecaster and strategist on international affairs, recently commented on the Navy’s vital role in this theater. He explained that the “balance of power in the Pacific between U.S. and Chinese naval forces remains key to American hegemony and the alliance that upholds it. In the event of war, more extreme and technological threats remain secondary to the conventional naval threat the U.S. poses to China and China poses to the U.S.”29George Friedman, “American Naval Policy and China,” Geopolitico Futures, January 22, 2025. The thinking behind his observation is a significant strategic factor that the Navy should have recognized independently and included in its NAVPLAN.

A time-tested military maxim says to tell your boss what you need to get the job done; second, tell your boss the consequences of not receiving what’s needed; and finally, make the best of what you have to accomplish the mission. The NAVPLAN studiously avoids specifying the consequences and the risks. For instance, it states, “Without substantial growth in Navy resourcing now, we will eventually face deep strategic constraints on our ability to simultaneously address day-to-day crises while also modernizing the fleet to enhance readiness for war both today and in the future.”30Franchetti, CNO Navigation Plan, 12.

What are these “deep strategic constraints” and what are the consequences and the risks caused by these constraints? The NAVPLAN provides no answers. These are critically important omissions and striking deficiencies. The NAVPLAN also states that the Navy is “continuing to advocate for the resources needed to expand all aspects of the Navy’s force structure necessary to preserve the peace, respond in crisis, and win decisively in war.”31Franchetti, CNO Navigation Plan, 12. This is a confusing and alarming statement. It appears to indicate that the Navy currently does not have a force structure that can “win decisively in war.”32Franchetti, CNO Navigation Plan, 12. If this is what the Navy is communicating, it is not done with transparency.

The 2024 NAVPLAN does explain the effects of an important planning factor that limits the Navy’s options for developing its readiness efforts for a possible war with China in 2027. The Navy has only one more budget cycle—the development of the fiscal year (FY) 2027 budget—to make any meaningful changes to its capabilities in preparation for a 2027 potential conflict. Consequently, the Navy’s existing fleet of ships, in terms of mix and numbers in 2024, is largely the fleet the Navy will have in 2027. This is a significant planning factor as the Navy addresses its readiness for 2027. As Donald Rumsfeld, a former secretary of defense, once famously stated, “As you know, you go to war with the army you have, not the army you might want or wish to have at a later time.”33Spencer Ackerman, “Donald Rumsfeld Wants to Give You the Most Ironic Life Lessons Ever,” Danger Room blog, Wired, May 14, 2013; and Ray Suarez, “Troops Question Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld about Armor,” PBS, December 9, 2004.

The 2024 NAVPLAN has a confusing relationship with a separate, but embedded, Navy initiative called Project 33. The NAVPLAN described this project as an effort to “get more ready players on the field by 2027,”34Franchetti, CNO Navigation Plan, III. and identified seven high-priority mitigations that the Navy needs to accelerate.35Franchetti, CNO Navigation Plan, II. By default, these seven actions became the NAVPLAN’s primary objectives, yet the Navy referred to these objectives as Project 33 and not NAVPLAN objectives, thereby muddying the waters about whether the NAVPLAN or Project 33 is the Navy’s overarching strategic guidance. In fact, Admiral Samuel Paparo, commander of the US Indo-Pacific Command, penned a January 2025 essay titled “Project 33 Is Enabling Joint All-Domain Operations in the Indo-Pacific”—and not “NAVPLAN Is Enabling Joint All-Domain Operations in the Indo-Pacific.” He wrote numerous sentences beginning with Project 33 such as “Project 33’s vision to provide more munitions will. . . ”36Admiral Sam Paparo, “Project 33 Is Enabling Joint All-Domain Operations in the Indo-Pacific,” US Naval Institute Proceedings 151/1/1,463 (January 2025). The lack of clarity between these documents only confuses the Navy’s two principal audiences.

The harmful effects of the NAVLAN’s lack of clarity and specificity are compounded by a similar set of deficiencies in higher-order national guidance. The Commission on Planning, Programming, Budgeting, and Execution (PPBE) Reform reported in March 2024 that the National Defense Strategy (NDS) was “not designed to be sufficiently specific enough to guide the programming phase of PPBE.” The commission’s report also stated that the Defense Planning Guidance was a “consensus-driven document that does not make hard choices, is overly broad, and lacks explicit linkages to prioritized goals, timeframes, risk assessments, and resource allocations.” The PPBE Reform report further stated these deficiencies did not provide “top-down guidance needed during the programming phase of PPBE.”37Robert Hale and Ellen Lord, Chair and Vice Chair, “Defense Resourcing for the Future, Commission on Planning, Programming, Budgeting, and Execution (PPBE) Reform,” Final Report, March 2024, 26. Inadequate and incomplete guidance, by the Defense Department and the Navy, undermines effective strategic and force-planning decision-making.

3. Lack of guidance on consequential issues

The 2024 NAVPLAN falls short of addressing critical high-level issues, leaving its two principal external audiences with an insufficient understanding of the Navy’s resource requirements. Given that the NAVPLAN is a prime tool for strategic communications and is the sole document to express the Navy’s way ahead to its external audiences, the scant commentary on key issues represents a missed opportunity for the Navy.

Key issue: A larger navy

While the 2024 NAVPLAN acknowledges the need for an on-the-record requirement for 381 crewed ships,38Sam LaGrone, “Navy Raises Battle Force Goal to 381 Ships in Classified Report to Congress,” US Naval Institute, July 18, 2023. This classified report was titled Battle Force Ship Assessment and Requirement. it did not explain why or when the Navy needs these ships. In 2025, the Navy has 297 battle force ships,39Ronald O’Rourke, “Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for Congress,” Report 32665, Congressional Research Service, September 24, 2024, 2, 56 (see Table G-1). with a shortfall of eighty-four ships. The document makes no attempt to communicate the strategic risk to the nation from the lack of warships, and it offers no plan B to offset the gap in assets. Furthermore, the Navy’s thirty-year shipbuilding plan for FY 202540This is the document’s informal but widely used title. Its formal title is Report to Congress on the Annual Long-Range Plan for Construction of Naval Vessels for Fiscal Year 2025. The Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, Deputy Chief of Naval Operations for Warfighting Requirements and Capabilities (OPNAV N9) prepared this document, and the Office of the Secretary of the Navy approved its release in March 2024. indicated that the Navy will “reach a low of 280 ships in fiscal year 2027,”41Michael Marrow, “Navy’s New 30-Year Shipbuilding Plan Sketches 2 Paths for Future Manned Ship Fleet,” Breaking Defense, March 19, 2024. the very year that the NAVPLAN directed the Navy to be ready for a possible war with China.

The lack of discussion on this significant matter is inexplicable. The unease is further increased with the realization that a global war with China in 2027 or even in 2030 will place impossible demands on the Navy to address multiple critical missions far exceeding its capacity. The Navy, as part of the joint force, will need to conduct, at a minimum, this sample of unprioritized missions:42This list builds on and updates the author’s “Ten Challenges to Implementing Force Design 2030,” which the Atlantic Council published in November 2023.

- Destroy Chinese naval and air forces invading Taiwan.

- Defend Japan, South Korea, and Australia from naval and air attacks.

- Isolate China from war-making resources—conduct economic warfare with blockade.

- Conduct horizontal escalation, i.e., destroy Chinese forces at Djibouti.

- Protect small amphibious ships inserting and extracting US Marine Corps stand-in forces inside Chinese weapons envelope.

- Protect sustainment of US Marine Corps stand-in forces inside Chinese weapons envelope.

- Protect US Marine Corps forces embarked in Navy large amphibious ships.

- Protect in transit Navy combat logistics forces sustaining Navy forces conducting distributed operations.

- Protect in transit Military Sealift Command forces sustaining Joint Force.

- Conduct homeland defense—continental United States, i.e., integrated air missile defense of critical seaports and Navy bases.

- Deter Russia as opportunistic adversary.

- Deter Iran as opportunistic adversary.

- Maintain surveillance of Chinese ballistic missile submarines.

- Maintain surveillance of Russian ballistic missile submarines.

- Maintain Navy strategic reserve to ensure combat credibility throughout war’s duration.

The Navy will be in a protracted war in a global conflict with China. While conducting those fifteen missions and the myriad other things required of the Navy, ships will incur far greater sustainment, maintenance, and repair requirements—further reducing the available numbers. In short, the Navy is likely to face a strategy-force mismatch. Ship numbers matter, and the US Navy does not have enough ships. As former Senator Sam Nunn (D-GA) once quipped, “At some point, numbers do count. At some point, technology fails to offset mass. At some point, Kipling’s ‘thin red line of heroes’ gives way.”43Charles L. Fox and Dino A. Lorenzini, “How Much Is Not Enough? The Non-Nuclear Air Battle in NATO’s Central Region,” Naval War College Review 33, no. 2 (1980).

Admiral Chas Richard, then-commander of the US Strategic Command, in a November 2022 speech made it very clear that the Navy lacked sufficient ships. He warned, “As I assess our level of deterrence against China, the ship is slowly sinking . . . it isn’t going to matter how good our [operating plan] is or how good our commanders are, or how good our forces are—we’re not going to have enough of them. And that is a very near-term problem.”44Caleb Larson, “‘Sinking Slowly’: Admiral Warns Deterrence Weakening against China,” National Interest, November 7, 2022. Note: Admiral Richard has since retired; he is the James R. Schlesinger Distinguished Professor at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center. Over the last two decades, however, no Congress and no administration, regardless of party, has attempted to fund a larger Navy. The nation cannot afford the number of ships the Navy says it needs to deter and defeat America’s potential enemies. The election of President Trump appears to have changed this calculus.

Key issue: Domain transparency

Another significant issue the 2024 NAVPLAN fails to address is the impact of surveillance technology on the changing character of war. This technology has increasingly made it easier to detect and target combatants on the oceans’ surface and aircraft in air space above it, calling into question the continued viability of manned ships and aircraft operating in such an environment. In a December 2022 essay, former Deputy Secretary of Defense Robert Work and former Google chief executive officer Eric Schmidt noted:

- One key change is that militaries will have great difficulty hiding from or surprising one another. Sensors will be ubiquitous, and once-impenetrable intelligence will be vulnerable to quantum advances in decryption. Highly adaptable and mobile weapons systems, including drones, loitering munitions, and hypersonic missiles will largely inhibit militaries from amassing forces to invade.45Eric Schmidt and Robert O. Work, “How to Stop the Next World War: A Strategy to Restore America’s Military Deterrence,” Atlantic, December 5, 2022. Note: Schmidt served as Google’s chief executive officer from 2001 to 2011.

In the 1930s, the US Navy experienced a similar change in the character of warfare as technological improvements increased the operational performance of aircraft carriers and the lethality of aircraft the carriers launched in terms of reliability, operating distance, and weight of bomb load. Eventually, this increased lethality (or relative combat effectiveness) surpassed the battleship’s lethality, and the Navy experienced a fundamental inflection point in its warfighting capabilities. The Navy observed this evolution of the aircraft’s increasing lethality but did not fully comprehend that the aircraft carrier and its aircraft’s steady progress would replace the battleship as the Navy’s capital weapon system. Not until actual combat—such as the Royal Navy’s November 1940 attack on the Italian Navy at its Taranto base,46The Royal Navy’s Fleet Air Arm’s 1940 attack on the Italian Navy in its Taranto Harbor was the first completely all-aircraft naval attack in history. Admiral Andrew Browne Cunningham, RN, the commander in chief, Mediterranean Fleet, stated: “Taranto should be remembered forever as having shown once and for all that in the Fleet Air Arm the Navy has its most devastating weapon.” and the Imperial Japanese Navy’s December 1941 attack on the US Navy in Pearl Harbor—did complete comprehension “sink in” about the carrier and its aircraft’s more lethal effectiveness.

Similarly, given the comments by Work, Grady, and others in this decade, the Navy faces another seminal inflection point if Chinese surveillance capabilities advance to make the oceans’ surface and the air space above it transparent. The implications for the continued viability of surface ships in such an environment are staggering. The Navy, however, appears to have bet its surface ships will still be viable in this enhanced surveillance environment and remains committed to its planned acquisition of replacement surface ships to include the Constellation-class frigates, Columbia-class ballistic missile submarines, Ford-class aircraft carriers, and the continuation of building Burke-class destroyers along with its acquisition plans to buy large numbers of unmanned surface platforms.

4. Lack of frankness

And so, today we find ourselves in an environment increasingly reminiscent of the late 1930s, where the overarching balance of power is becoming ever-less stable, and where the difference between peace and a multi-theater system-transforming war will likely hinge on whether the United States and its allies can sustain the ever-more tenuous regional balances.

—Andrew A. Michta, “The United States Must Revisit the Basics of Geostrategy,” 19FortyFive.

Today is like 1938. Indeed, Franchetti has said so, but omitted her prescient comments from the 2024 NAVPLAN. As the vice CNO, she commented that the 1930s was a decisive decade that “rhymes in some key ways” with today’s security environment: She noted that both eras reflect periods of constrained defense spending, reduced construction of Navy ships, and a growing disparity in the capability and capacity between the US Navy and its principal adversaries—Imperial Japan in the 1930s and the authoritarian People’s Republic of China in the 2020s—resulting in a US fleet that was “too small and insufficiently resourced for total war,”47Lisa Franchetti, Remarks of the then-Vice Chief of Naval Operations, SENEDIA’s Defense Innovation Days, Newport, Rhode Island, August 29, 2023. and ineffective for deterrence. She is in excellent company. Kaja Kallas, then-prime minister of Estonia and now the European foreign policy chief, has reasoned that the current global security environment reflects 1938, “when a wider war was imminent, but the West had not yet joined the dots.”48Patrick Wintour, “‘We’re in 1938 Now’: Putin’s War in Ukraine and Lessons from History,” June 8, 2024. Dr. Hal Brands, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute,49Dr. Brands is the Henry A. Kissinger Distinguished Professor of Global Affairs at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies. He is also a columnist for Bloomberg Opinion. Dr. Brands has previously worked as special assistant to the secretary of defense for strategic planning and lead writer for the National Defense Strategy Commission. has also commented on the striking parallels between today’s geostrategic events and those of the 1930s. Ominously, the Commission on the National Defense Strategy concluded in July 2024 that the “US military lacks both the capabilities, and the capacity required to be confident it can deter and prevail in combat.50Harman and Edelman, Commission on the National Defense Strategy Report, VII.The Wall Street Journal wrote a sober editorial saying, “The world today is more like the late 1930s, as dictators build their militaries and form a new axis of animosity, while the American political class sleeps.”51Editorial Board, “A Clarion Call for Rearmament,” Wall Street Journal, June 3, 2024.

This security environment demands frankness of expression about the threats, risks, and defense requirements by US senior military leaders. There isn’t much public evidence of US senior military leaders providing candid expression. In May 2024, US Senator Roger Wicker (R-MS) cautioned in a New York Times commentary, titled “America’s Military Is Not Prepared for War or Peace,” that:

- When America’s senior military leaders testify before my colleagues and me on the US Senate Armed Services Committee behind closed doors, they have said that we face some of the most dangerous global threat environments since World War II. Then, they darken that already unsettling picture by explaining that our armed forces are at risk of being underequipped and outgunned.52Roger Wicker, “America’s Military Is Not Prepared for War—or Peace,” New York Times, May 29, 2024.

The notable exception is General D. W. Allvin, US Air Force and the current chief of staff, who stated in January 2025 that, “As the arc of the threat increases daily, it is my assessment this risk is unacceptable and will continue to rise without substantially increased investment.”53David W. Allvin, “Allvin: It’s Make or Break Time. America Needs More Air Force,” Breaking Defense, January 17, 2025. Perhaps all current service chiefs share the same opinion about their individual service, but if they do, they are not speaking up and out.

Lack of frankness is a Navy practice

In its public congressional testimony, the Navy’s posture statements submitted in April and May 2024 to the House and Senate Armed Services Committees and to the House and Senate Appropriations Subcommittees on Defense do not reflect any discussion of “at risk of being underequipped and outgunned.” In the two instances that the word “risk” is used in these statements, it is associated with “sealift investments” and “installation investments.”54Lisa Marie Franchetti, “Statement on the Posture of the United States Navy,” Senate Committee on Appropriations, April 16, 2024; and Lisa Marie Franchetti, “Statement on the Posture of the United States Navy in Review of the Defense Authorization Request for Fiscal Year 2025 and the Future Years Defense Program,” Senate Armed Services Committee, May 16, 2024. On page six of both statements, under Sealift Investments, is the following: “The Buy-Used program provides a stable acquisition profile with forecasted maintenance and repair costs to meet strategic mobility requirements at a moderate level of risk.” On page twelve of both statements, under Installation Investments, is the following: “We are investing in our critical utility systems, upgrading water, wastewater, and electrical generation, distribution, and treatment capabilities to improve resiliency, quality, and reliability and minimize risk to mission.”

Indeed, the Navy’s 2024 posture statements to Congress are very upbeat documents with statements such as: “In every ocean, we uphold and protect the post-World War II rules-based international order that we fought to establish and have continued to defend for nearly three-quarters of a century.” This is clearly not true for the Red Sea. Well before the publication of the posture statements, the Houthis waged an effective sea denial campaign that the US Navy was unable to prevent. These posture statements do add that the Houthis have disrupted “the free flow of maritime commerce in the Red Sea.” As reported by General Christopher Mahoney, the assistant commandant of the Marine Corps, “The Houthi’s sea-denial campaign has altered global trade routes, imposed global economic costs, enhanced its international profile, and perhaps most importantly tied up a significant portion of American naval power at a time when demand for our naval ships outstrips supply.”55Christopher Mahoney, “Four Lessons on Sea Denial from the Black and Red Seas,” Defense News, June 18, 2024. There is, however, no discussion in the Navy’s 2024 posture statements of the implications of this Houthi warfare campaign on the Navy’s force structure, weapons, operational concepts, readiness, etc. Nor is there a mention of the high cost of fighting the Houthis and defending Israel.56In October 2024, Jake Epstein reported, “Navy warships and aircraft on station in and around the Middle East expended $1.85 billion in munitions on fights in the region between October 7, 2023, to October 1, 2024, a Navy spokesperson confirmed to Business Insider on Thursday. The $1.85 billion accounts for hundreds of munitions launched from US warships and aircraft attached to them, including surface-to-air interceptor missiles, land-attack missiles, air-to-air missiles, and air-to-surface bombs. Some of these weapons cost several million dollars apiece. The substantial figure covers the Navy’s campaign against the Houthis in the Red Sea, which is ongoing, and its efforts to defend Israel from attacks by Iran and its proxies.” See Jake Epstein, “The US Navy Fired Nearly $2 Billion in Weapons Over a Year of Fighting in the Middle East,” Business Insider, October 31, 2024. Likewise, there is no treatment of the implications of naval warfare by the Ukrainian Navy’s use of unmanned surface vessels (i.e., drones) to its highly effective sea denial campaign against the Russian Navy in the Black Sea.

Despite affirming that the Navy needs more ships to meet its mission in this decade, the Navy’s posture statements profess that the president’s FY 2025 budget submission for the Navy “funds a strong, global Navy that is postured and ready to deter potential adversaries . . . [and] win decisively in war.”57Franchetti, “Statement on the Posture of the United States Navy,” and “Statement on the Posture of the United States Navy in Review of the Defense Authorization Request for Fiscal Year 2025 and the Future Years Defense Program,” 4: “The Navy’s budget request for FY25 funds a strong, global Navy that is postured and ready to deter potential adversaries, protect our homeland, respond in crisis, and, if called, win decisively in war.” The documents conclude that the Navy “continues to meet its Title 10 mission to be organized, trained, and equipped . . . for prompt and sustained combat incident to operations at sea.”58Franchetti, “Statement on the Posture of the United States Navy,” and “Statement on the Posture of the United States Navy in Review of the Defense Authorization Request,” 14: “The Navy continues to meet its Title 10 mission to be organized, trained, and equipped for the peacetime promotion of the national security interests and prosperity of the United States and for prompt and sustained combat incident to operations at sea.”

These statements are disconcerting. If the Navy is funded and postured to deter and win per the April and May 2024 posture statements, it is ambiguous if these statements contradict or support the Navy’s formal requirements for 381 crewed ships. Furthermore, it is worrisome that the Navy plainly states that it can deter and win, while the July 2024 report by the Commission on the National Defense Strategy states: “The Joint Force is at the breaking point of maintaining readiness today. Adding more burden without adding resources to rebuild readiness will cause it to break.”59Harman and Edelman, Commission on the National Defense Strategy Report, 64. Moreover, the report adds, “The nation was last prepared for such a [global] fight during the Cold War, which ended 35 years ago. It is not prepared today.”60Harman and Edelman, Commission on the National Defense Strategy Report, V

Communicating frankness with integrity and without offense

Two 1970s exemplars are instructive. In their back-to-back tenures as the Navy’s service chiefs, CNO Elmo Zumwalt and CNO James L. Holloway III confronted declining budgets, shrinking numbers of ships, plummeting readiness levels, and growing Soviet military capabilities. Moreover, things went from bad to worse during President Jimmy Carter’s administration. While President Gerald Ford proposed to Congress in 1977 the construction of 157 new ships, his successor, Jimmy Carter, in 1978 proposed only 70.“61Francis J. West, Jr., “Planning for the Navy’s Future,” US Naval Institute Proceedings 105/10/920 (October 1979). From 1981 to 1983, West was assistant secretary of defense for international security affairs, US Department of Defense. The collective time Zumwalt and Holloway held office has “become known to American history as the post-Vietnam ‘hollow force.‘”62John T. Kuehn, PhD, “Zumwalt, Holloway, and the Soviet Navy Threat: Leadership in a Time of Strategic, Social, and Cultural Change,” Marine Corps University Press, Journal of Advanced Military Studies 13, no. 2 (Fall 2022). The two CNOs knew what had to be done. They had to lead and communicate frankly the issues confronting the Navy—issues no different from those challenging the Navy in 2025.

Zumwalt, in 1971, calculated the Navy had a 45 percent chance of defeating the Soviet Navy in a conventional war at sea. One year later, as he drafted the Navy’s FY 1973 budget, he reevaluated the chances at 35 percent.63John T. Kuehn, Zumwalt, Holloway, and the Soviet Navy Threat Zumwalt stated in a 1971 US News & World Report interview, “If the US continues to reduce and the Soviet Union continues to increase, it’s got to be inevitable that the day will come when the result will go against the US.”64Elmo Zumwalt, “Where the Russian Threat Keeps Growing,” Interview, US News & World Report, September 13, 1971, 72. In June 1975, Holloway on the pages of the US Naval Institute Proceedings wrote:

- We have been decommissioning ships faster than we have been building new ones. And although today we can accomplish the naval tasks of our national strategy, in some areas it is only with the barest margin of success. As Soviet maritime capabilities continue to increase, it is clear to me, as it must be apparent to you, that it is essential to reverse the declining trend of our naval force levels.65James L. Holloway III, “The President’s Page,” US Naval Institute Proceedings 101, no. 6 (June 1975): 3.

These two CNOs, “did not shy away from noticeably outlining the threats, challenges, and shortcomings of the fleet;” they unhesitatingly alerted the nation to the “security and technological dangers of a seemingly new age.”66Holloway III, “The President’s Page.” In short, Zumwalt and Holloway provided leadership underwritten with intellectual and moral courage to sound a clarion call about the Navy’s declining readiness posture. For their integrity and forthrightness, their civilian bosses did not censure them.

The American public saw similar CNO leadership in January 2015 when Jonathan Greenert testified before Congress about the effects of sequestration on the Navy’s readiness to execute the Defense Strategic Guidance. He concluded that the Navy could not “confidently execute the current defense strategy within dictated budget constraints.”67Hearing on National Defense Before the Senate Armed Services Committee, 114th Cong. (2015) (statement of Jonathan Greenert, Admiral, US Navy, Chief of Naval Operations, 4-5). The full quote is: “There are many ways to balance between force structure, readiness, capability, and manpower, but none that [the] Navy has calculated that enable us to confidently execute the current defense strategy within dictated budget constraints.” Greenert accompanied his testimony with a table displaying the ten missions the Defense Strategic Guidance required and the associated risk for each mission caused by sequestration. See figure 2, which depicts the key portion of Greenert’s table. His table showed two missions in red highlighting that the Navy could not execute and five missions in yellow highlighting that were “high risk” for the Navy.68Hearing (Greenert, 4, 5, and 9). Greenert declared that naval forces “will not be able to carry out the Nation’s defense strategy as written.” His assessment finished with a dire warning that when facing major contingencies, the Navy’s “ability to fight and win will neither be quick nor decisive.”69Hearing (Greenert, 4, 5, and 9).

Figure 2: Excerpt of CNO Greenert’s assessment of 2015 mission impacts to a sequestered US Navy

| Quadrennial defense review objectives | Defense strategic guidance missions | Navy ability to execute |

|---|---|---|

| Project power and win decisively | Project power against a technologically capable adversary | Major challenges to achieve warfighting objectives in denied areas: • Inadequate power projection capacity • Too few strike fighter, command/control, electronic warfare assets • Limited advanced radar and missile capacity • Insufficient munitions |

| Execute large-scale ops in one region, deter another adversary’s aggression elsewhere | Limited ready capacity to execute two simultaneous large-scale ops: • 2/3 of required contingency response force (2 of 3 Carrier Strike Groups and 2 of 3 Amphibious Readiness Groups) not ready to deploy within 30 days |

|

| Conduct limited counterinsurgency and other stability operations | Increased risk due to: • Reduced funding to Navy Expeditionary Combat Command • Reduced ISR capacity (especially tactical rotary wing drones) |

|

| Operate effectively in space and cyberspace | This mission is fully executable in a sequestered environment: • Navy continues to prioritize cyber capabilities |

5. Lack of a serious format for a serious document

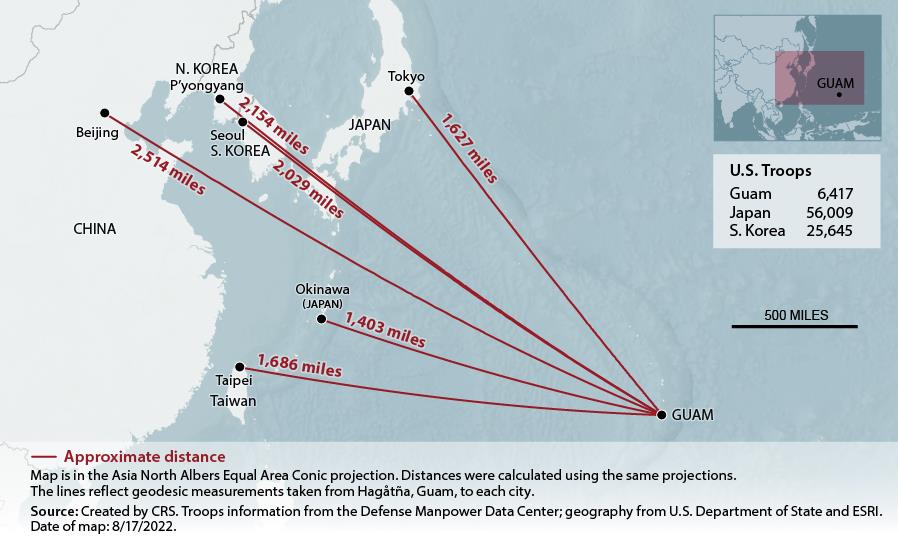

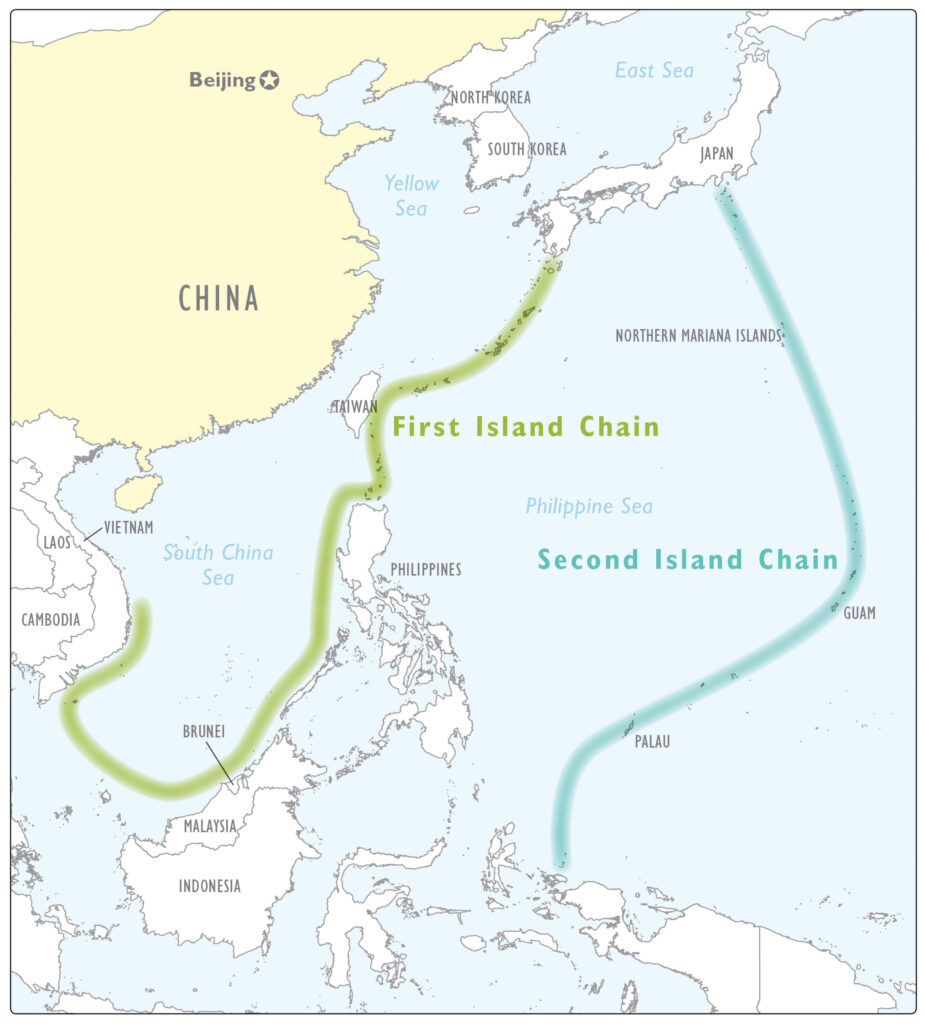

With no maps of maritime terrain or tables of hard net assessment data and the inclusion of too many “eye candy” glossy images of kit, the 2024 NAVPLAN has the look and feel of a coffee table publication, meant for casual and light reading with limited analysis and a superficial approach to naval strategic planning. Serious people produce serious documents. The NAVPLAN’s format signals an indifferent document, unlike the formats used for the National Security Strategy. The lack of hard data on net assessment is a significant weakness, especially the lack of maps, which help make the relationship between sea power and physical space evident. Indeed, understanding maritime geography “facilitates communication and strategic thinking and can help construct a compelling public narrative in support of [Navy] policy.”70Andrew J. Rhodes, “The Geographic President: How Franklin D. Roosevelt Used Maps to Make and Communicate Strategy,” Washington Map Society’s Portolan, Spring 2020. This essay won the 2019 Ristow Prize for Academic Achievement in the History of Cartography. Rhodes is a career civil servant who has served as an expert in Asia-Pacific affairs in a variety of analytic, advisory, and staff positions in the US government. He is an affiliated scholar of the China Maritime Studies Institute at the US Naval War College. Rhodes also commented that geography provides “leaders with a broader set of tools for analyzing complex problems, developing options within a team, and presenting a public vision for a decision.” The below figures illustrate the type of maps to include in a serious strategic planning document. Figure 3 depicts the “tyranny of distance”71Rhodes, “The Geographic President”: “In 1942, FDR ordered Secretary of War Henry Stimson to come to the Map Room on a Sunday afternoon for what FDR called a ‘geography lesson.’ FDR asked him to move his wheelchair to the map of the Pacific where he criticized a recent memorandum from Stimson that failed to consider the tyranny of distance in the Pacific.” in the Indo-Pacific theater, and figure 4 shows the strategic importance of the “first island chain” in effectively “containing” China.

Figure 3: Western Pacific maritime geography: Tyranny of distance, lack of US strategic depth

Figure 4: The first island chain’s strategic importance in preventing the Chinese navy from entering the Pacific and Indian oceans

Conclusion: Course corrections for a 2025 NAVPLAN

The biggest things that happen in the Navy are winning the battles in the [Joint Chiefs of Staff], the Secretary of Defense’s office, the White House, and Congress. We have to convince all these people; otherwise, we lose. What we need is a lawyer [as CNO], preferably a New York lawyer . . . He doesn’t have to know a lot about the Navy; he has to know how to win arguments.

Admiral William J. Crowe Jr., quoted in History of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, 1915-2015 by Thomas C. Hone and Curtis, A. Utz.

As the Navy’s senior strategic leader,72Peter M. Swartz and Michael C. Markowitz defined CNO responsibilities as follows: “Prepare the way for developing a Program Objective Memorandum for the Future Year Defense Program; develop and submit an annual Program Objective Memorandum and budget to the Office of the Secretary of Defense and Congress; man, train, equip and support the existing fleet and shore establishment, and maintain its readiness; conduct long-range planning beyond the Future Year Defense Program; provide national security policy, strategy and operational advice to the President and Defense Secretary, and Chairman JCS; articulate the Navy story; organize (and re-organize) the fleet and shore establishment; represent the Navy in joint, bilateral, and multilateral fora; and take good care of Navy men and women.” See Peter M. Swartz and Michael C. Markowitz, Organizing OPNAV (1970 – 2009), Strategic Studies Division, Prepared by CNA for the US Navy Naval History and Heritage Command, CAB D0020997.A5/2Rev, January 2010, Slide no. 11. the CNO must: “(1) get the big ideas right; (2) communicate those ideas effectively; (3) oversee the implementation of the ideas, and (4) determine how to refine the big ideas and then repeat the cycle.”73Bill Snyder, “Gen. David Petraeus: Four Tasks of a Strategic Leader,” Insights, Stanford Graduate School of Business, May 14, 2018. The Navy’s “big ideas” address its national defense role and the requisite force structure to support that role.

When first published in September 2024, the NAVPLAN correctly got the Navy’s big ideas right. The arrival of a new commander in chief in January 2025 changed the nation’s defense priorities, and now the Navy must replace its NAVPLAN with a version aligned with President Trump’s priority to build ships for the Navy. The president superseded the Navy’s priorities in the order of readiness, capability, and capacity. Far from being an onerous burden for the Navy to craft a new 2025 NAVPLAN, the nation’s other armed services should be so fortunate.

In addition to embracing the president’s direction, the new 2025 NAVPLAN should address the deficiencies outlined in this paper. While retaining its commendable attributes, especially its strategic objective to concentrate on “readiness for the possibility of war with the People’s Republic of China by 2027,” the 2025 NAVPLAN should incorporate the following course corrections:

- Increase its focus on the Navy’s two most important and influential audiences by addressing their information needs. They require a description of a possible war with China and Russia and how the Navy, as part of the Joint Force, would prevail. Such a sobering, informative description is not a multivolume addition but an executive summary with sufficient detail for these audiences to grasp the broad outlines and scope of a conflict and the implications for the Navy. The description must contain Chinese and Russian capabilities and numbers, logistic challenges, key military problems to overcome, and the role of allies and partners illustrated with maps and net assessment tables.

- Improve clarity and specificity by providing the context of “why” and “how” the Navy intends to achieve its strategic objectives. Such context provides substance to the NAVPLAN and eliminates the use of assertions, which are a form of self-serving rhetoric, often informally called “happy talk.” In addition, the NAVPLAN must list the strategic assumptions the Navy used to craft the documents and address the implications of risk.

- Address the Navy’s approach to resolving its other consequential issues—besides the need for a larger Navy and domain transparency—such as the ongoing depletion of ordnance war stocks for kinetic operations in the Middle East,74Justin Katz, “INDOPACOM’s Paparo Acknowledges Stockpile Shortages May Impact His Readiness,” Breaking Defense, November 20, 2024; see also Epstein, “The U.S. Navy Fired Nearly $2 Billion in Weapons.” the slow and painful development of directed energy weapons,75Cal Biesecker, “Still Unhappy with Progress on Directed Energy Weapons, SWO Boss Wants More Land Based Testing to Speed Use on Ships,” Defense Daily, January 14, 2025. and the yearslong debate over the acquisition of the medium landing ship.76Geoff Ziezulewicz, “Navy Now Seeking Commercial Ship Design to Propel Its Long-Delayed Medium Landing Ship Program Forward,” War Zone, January 15, 2025. Note: The medium landing ship (designated as the LSM) is a new class of Navy amphibious ships to support the Marine Corps conducting its operational concept to set up ad hoc bases on islands, fire anti-ship missiles in a potential conflict, and quickly move to new locations. The Navy envisions a ship length of 200 to 400 feet; a draft of 12 feet; a crew of about seventy sailors; and a capacity for carrying fifty Marines and 648 short tons of equipment. This ship would have a transit speed of 14 knots and a cruising range of 3,500 nautical miles, as well as a roll-on/roll-off beaching capability and a helicopter landing pad. The 2025 NAVPLAN must forthrightly treat these issues head-on, lucidly conveying the implications, risk, assumptions, and mitigations.

- Advance frankness by fully reflecting the Navy’s leadership philosophy of “Get Real, Get Better,” which requires Navy leaders to “be honest about our abilities and be fully transparent about our performance.”77As mentioned in the introduction, Admiral Lescher, then-vice chief of naval operations, explained the crux of the Navy’s new “Get Real, Get Better” initiative during a May 2022 speech, saying: “We have to self-assess and be our own toughest critics. We need to be honest about our abilities and be fully transparent about our performance. Once we ‘embrace the red,’ we will be able to identify solutions and more realistically predict our mission readiness.” See “Vice Chief of Naval Operations Talks,” US Navy Press Office. The Navy must speak frankly about how US adversaries, especially China, are harming US national interests and set forth a well-crafted message to explain how the Navy—properly resourced to be lethal and ready—will preserve the nation’s security in an increasingly dangerous world. The Wall Street Journal Editorial Board maintains that the United States “is slouching ahead in blind complacency until China invades Taiwan or takes some other action that damages US interests or allies because Beijing thinks the United States can do nothing about it.”78Editorial Board, “‘The Big One Is Coming’ and the US Military Isn’t Ready,” Wall Street Journal, November 4, 2022. The Navy should not partake in “blind complacency.” The threats to the United States are all too real.

- Turn the NAVPLAN into a serious strategic planning document, produced by serious people, shedding the look of a coffee-table book or public-affairs handout. Eliminate all “glossy” images of ships and airplanes in the document and replace them with graphics that are relevant to and useful for the Navy’s two principal audiences as well as force planners and strategists of all ilk: maps depicting maritime terrain and net assessment tables regarding China and Russia in particular.

Collectively these Navy course corrections to the NAVPLAN will enable all Navy audiences to better grasp the severity of the security threats confronting America and comprehend the Navy’s funding requirements. With greater candor, explicitness, and detail—and amply illustrated with maps and tables depicting hard-threat data—the 2025 NAVPLAN can, indeed, demonstrate that clarity is power.

About the author

Bruce Stubbs had assignments on the staffs of the secretary of the Navy and the chief of naval operations from 2009 to 2022 as a member of the US senior executive service. He was a former director of Strategy and Strategic Concepts in the N3N5 and N7 directorates. As a career US Coast Guard officer, he had a posting as the Assistant Commandant for Capability in Headquarters, served on the staff of the National Security Council, taught at the Naval War College, commanded a major cutter, and served a combat tour with the US Navy in Vietnam during the 1972 Easter Offensive. The author drew upon his forthcoming publication, Cold Iron: The Demise of Navy Strategy Development and Force Planning, to compose portions of this commentary.

The views expressed are the author’s and do not represent those of any organization or affiliation.

Related content

Explore the program

Forward Defense, housed within the Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security, generates ideas and connects stakeholders in the defense ecosystem to promote an enduring military advantage for the United States, its allies, and partners. Our work identifies the defense strategies, capabilities, and resources the United States needs to deter and, if necessary, prevail in future conflict.

Image: A US Navy Sailor launches an F/A-18E Super Hornet from the “Blue Diamonds” of Strike Fighter Squadron (VFA) 146 from the flight deck of the aircraft carrier USS Nimitz (CVN 68). US Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Joseph Calabrese)