If the Covid-19 era has taught us one thing about ourselves and our fellow humans, it’s that we really like coffee. More proof came on a Tuesday in early September last year when Pret a Manger launched its in-shop coffee subscription YourPret Barista. For £20 a month, you could have five drinks a day, every day, including coffee, tea and smoothies (redeemed with at least 30 minutes between each drink order). Pret had been expecting 2,000 or at a push 3,000 people to sign up on the first day. By 3pm, the scheme had already topped 15,000 subscribers.

Clare Clough, Pret’s managing director in the UK, insists this was a pleasant surprise and that, not for a second, did the company wonder if it had undervalued its new offering. “Absolutely not,” she says. “One of the big reasons we started the coffee subscription was that when we reopened our first 10 shops after [the first] lockdown, we saw people posting on Instagram this moment of being reunited with their Pret coffee. People were holding it aloft like it was a football trophy or something. And we wanted to celebrate that by offering a value-for-money proposition that was almost too good to be true.”

Almost too good to be true is right. If you bought two £2.75 lattes (Pret’s most popular sale) a week, the subscription would pay for itself. On Twitter, Jonathan Allenby, a data consultant from St Albans, posted a link to a calculator that allowed you to input your Pret orders and showed how much you would save. Allenby, a Pret user with a six-drinks-a-week habit, found he was recouping £62.77 a month. But if you ordered five frappés a day, seven days a week, you would benefit from a monthly saving of £556.33, or £6,675.96 annually.

The new subscription was certainly a roll of the dice for Pret, which had endured a very challenging pandemic. In July, two months before it launched the scheme, the sandwich chain announced it was closing 30 shops and losing one-third of its 8,800 staff. Pret will not reveal how many customers currently take advantage of the subscription, only, says Clough, that the numbers are “in line with the targets we set ourselves, but those targets were stretching. So we’re very pleased with the results.”

The take-up for Pret’s new deal hints at something else we learned about ourselves during the lockdowns: British consumers do not fear a subscription. Our gateway drugs might be Netflix or Disney+ or Spotify, even the Guardian and Observer (in which case, thank you), but before you know it, the doorbell rings and it’s your monthly cheese subscription from Neal’s Yard Dairy or you are wondering when your quarterly delivery from the London Sock Exchange will turn up. Freddie’s Flowers (“I’m like the milkman but with flowers”) had 60,000 active customers in March 2020 before the first lockdown for its weekly flower subscription; one year on, it had more than 110,000 regulars and a turnover of £30.3m.

This goes against the grain of what economists might anticipate. Faced with a precarious financial outlook, you would imagine we would become cautious, trim any unnecessary expenditure (and it might be a stretch to justify cheese or flowers as essential purchases). In fact, the little dopamine pop of retail therapy has been hard to resist for many of us during the past year. According to research by Barclaycard, Britain is now “a nation of super subscribers”, spending £323m in 2020 on digital and subscription services, an increase of 39.4% on the previous year. The average household now has seven contracts and it might be worth keeping an eye on the mission creep in your bank account: men typically spend £57 a month (£684 a year); women on average outlay £35 each month (£420 annually).

The most popular subscriptions hook us on one or even two of the three “S”s: security, savings, surprise. “Security” is the most quotidian. Perhaps early on in the pandemic, you ran out of lavatory paper and decided that you’d rather not be caught with your trousers down again. You find a company you like, say Who Gives a Crap or Cheeky Panda, and you basically wait for the rolls to roll in. This could apply to anything you use regularly and don’t have a strong opinion on, from shampoo to protein powder to printer ink. There might be a financial saving too, but the main appeal is the convenience of not having to put on a mask and go into a shop or remembering to order online.

“Savings” is what a subscription such as YourPret Barista promises. It’s clear – and understandable – that customers want to feel that they are getting a good deal for their investment and their loyalty to a service. This is the case even with the most premium offerings, such as the exercise company Peloton, one of the big winners in lockdown. Before you splash out on a Peloton stationary bicycle or treadmill costing up to £2,295 – plus £39 a month for membership – you are encouraged to compare your existing fitness costs and travel time with the new, home-based gym set-up you would enjoy. After answering a few questions online you get a five-year plan informing you how soon the equipment will “pay for itself” and the number of precious travelling hours you will save.

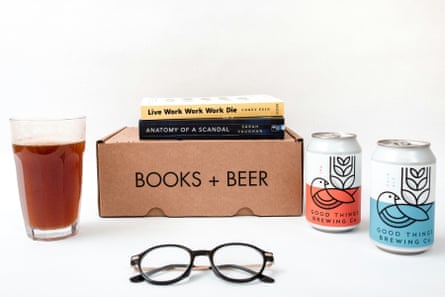

But a real boom growth category during the pandemic has been “surprise” subscriptions. Many of these are aimed at open-minded culture vultures. For example, for £15.95 each month, The Retro store in Glasgow will send you a box of three cassette tapes from “the 1980s and beyond” – or comics, games or vinyl – hand-picked by its tastemakers. Books + Beer does what it says on the tin: a couple of craft ales and a new work of crime or nonfiction.

“A lot of the subscriptions that have done particularly well this year are focused on the self-care aspect,” says Alice Revel, who started Books + Beer a couple of years ago and has seen subscriber numbers swell by around 40% in the past year across three different monthly book packages that she curates. “They’re experiential, whether it’s inviting you to sit down and have a couple of craft beers and read your book or make some cocktails or cook some pasta or whatever. When pretty much all the news that you’re receiving is fairly negative, something nice coming through the post box really can make a day a little bit better.”

It’s easy to see why these regular, recurring deliveries have thrived in the Covid age. “The subscription boom is fuelled by the monotony of lockdown and people feeling like they want joyful reoccurring moments with brands,” says Hayley Ard, cultural anthropologist at Portas, Mary Portas’s creative agency. “Two years ago, if you’d asked me if I’d join a shedload of subscription services, I’d have laughed. But the cultural dial has shifted – now we’re totally cool with having five or six different deliveries a week. It feels manageable, sometimes even magical.”

Ard selects Pret, Estrid’s razors for women and Bother, which promises “fast delivery of boring basics”, such as washing powder and nappies, as companies that bring “subscription joy”. And she’s in no doubt that these offers will remain a key part of how we shop, even when we venture out more. “Right now, subscription services are split between those that offer supreme utility and those that dial up joy – the truly delightful options that bring a moment of wonder to our weeks,” says Ard. “Yes, the ones in the middle will peter out. But the rest? They’re not going anywhere.”

Subscriptions are not new, but what we are seeing in 2021 is an unprecedented range of companies – large and small – which are making it a central part of their business strategy. Barclaycard found that 10% of companies unveiled their first subscription service between March and June 2020. And they keep coming: last week, the suit retailer Moss Bros launched Moss Box, which allows subscribers to choose two items of casual or formal wear for £65 a month, with unlimited, free swaps. Its CEO, Brian Brick, hopes, perhaps optimistically, that the company will become “the Netflix of fashion”.

Another newcomer to the subscriber game is Volvo, the Chinese-owned, Swedish-DNA car company that launched Care by Volvo in the UK last September. You might justifiably wonder: how do you subscribe to a car? Isn’t leasing – what’s known as a PCH or personal contract hire – basically the same thing? The difference, Kristian Elvefors, the managing director of Volvo Cars UK explains, is one of flexibility. A car subscription tends to be more expensive, but Care by Volvo allows you to change your car or cancel your agreement with three months’ notice (a typical PCH might last three years). The price quoted, which start from £559 per month for a small Volvo SUV, is all-inclusive and allows you to add insurance or use your own.

“In the UK, we love our cars,” says Elvefors. “We love to have several cars, if we can afford to. And we like to change them quite often. We like to explore, we like to test, but not necessarily own. Subscription is a product for the future, that’s for sure.”

Care by Volvo is proving popular, Elvefors reports: having previously had success with it in Europe, subscriptions now make up 8% of Volvo’s total retail sales. Perhaps most importantly for the carmaker, however, it attracts a new customer base to the brand, proving especially popular in the 45- to-55-year-old age range, a decade younger than Volvo’s traditional owner. Clough reports the same trend with Pret’s coffee subscription. “We’ve been having more young people in our shops than we might have previously had,” she notes. Subscriptions used to have a fusty reputation, of Reader’s Digests piling up without being read. But millennials, maybe encouraged by YouTube, where subscribing costs nothing, seem to show little reluctance about signing up.

For the companies themselves, offering subscriptions is a no-brainer. They bring in predictable and regular revenue and the relationship invariably results in greater brand loyalty. Multinationals have clearly taken note. Last November, Nestlé acquired a majority stake in Mindful Chef, whose weekly delivery of recipe kits boomed into a £50m business during the pandemic. The fee was undisclosed, but around the same time, Nestlé also bought Freshly, the US meal-delivery service for $950m.

Subscriptions are even more valuable now because of the data that can be harvested from an ongoing relationship with customers. The inspiration for Pret’s coffee subscription came from the US chain Panera Bread, which is also owned by its parent company JAB Holding, the Luxembourg-based food conglomerate. Panera introduced its deal pre-pandemic, in February, charging $8.99 (around £6.50) per month for unlimited drip coffee (one cup every two hours). By last summer, it had more than 800,000 subscribers.

Clough describes YouPret Barista as “our first digital relationship with our customers”. In Pret’s early days, the company, under founders Sinclair Beecham and Julian Metcalfe, was known for its offbeat creations and marketing. Now each time subscribers pick up a drink they will scan a QR code that collects information about their purchases. The goal is “recurring revenue” and here again the model is Panera, which has a database of more than 40m customers across the United States.

“We think of it in terms of a lifetime value of a customer, not transaction by transaction,” Panera’s chief brand and concept officer, Eduardo Luz, told the business magazine Forbes last year. “When you think of it in those terms, we know a subscriber will consume six to 10 more times with Panera over their lifetime than one who is not a subscriber. That’s the logic we’re unleashing.”

Depending on how you feel about data being collected on your purchases – Pret insists that it will always ask for permission – subscriptions do not represent a particularly risky or sinister proposition for most consumers. Martin Lewis-types would probably, wisely, recommend keeping track of the direct debits that are leaving our bank account each month. Also occasionally asking yourself if you really need Netflix, Prime Video, Disney+ and Now TV.

Volvo’s Elvefors acknowledges this is a potential issue. “I’m worried something is happening to me,” he admits. “I can’t control all the 20 or 30 subscriptions I have. My bank account will be empty quite quickly if I don’t stop it!” Then he adds: “But hopefully you’ll realise you have a Volvo in your driveway.”

For the businesses, the main concern is setting a price that is attractive enough to lure people in, while also providing strong returns for their bottom line. A week after Pret launched its coffee subscription, the healthy fast-food chain Leon started to offer “unlimited” (actually 75) coffees for £15 over a 30-day period. Then, in February this year, Pret announced it was removing smoothies and frappés, which have expensive ingredients and are time-consuming to make, from the subscription package. But after complaints, it hastily backtracked: “We’ll never be too proud to admit when we’ve not got it quite right,” a statement read.

As more of us return to our offices, Clough insists that Pret is unfazed by other coffee deals. “We’ll always welcome a bit of healthy competition in the marketplace,” she says. Moreover, she insists the subscription, as with subscriptions more generally, is not going anywhere. “No, no, it’s very much part of our offer going forward,” Clough goes on. “YourPret Barista is here to stay.”

It’s in the post: a selection of subscriptions

The London Sock Exchange Each quarter, for £75, three pairs of new, playful socks (each knitted with 200 needles to make them super-comfortable and strong) will arrive in letterbox-friendly packaging. But no sock lasts forever, so you can also refill the box with old or unwanted pairs and they will be recycled by the company free of charge.

Cattitude Box Yep, a subscription box for cats (and their “cat mums and dads”). Each month, for £31.95, you will receive three to four cat-related items for yourself, and three to four goodies for your furry friend. Think chew treats, mugs, purses – just make sure you divvy them up correctly.

Birchbox There’s a near-overwhelming variety of beauty subscription boxes (luxury, vegan, problem skin and many more). One of the best all-rounders is Birchbox, founded in 2010. Each month, for £13.95, you will be sent five deluxe sample and travel-sized beauty products, and sometimes a full-size one, packaged in Birchbox’s sleek Insta-famous boxes.

Sous Chef Monthly Tasting Box A box of weird and wonderful foods for £27.50. Expect a mix of the super-seasonal and store-cupboard staples, such as lemon-infused tagliatelle and tonka beans. Plus each month a you get “secret weapon”: an ingredient you will use time and again.

Craft Gin Club Booze subscriptions boomed in lockdown, presumably not unconnected with home schooling. Craft Gin Club has done especially well with its monthly selection of a (large, no miniatures here) bottle of gin from small-batch distilleries, plus mixers for your G&T and assorted treats, all for £40.

Old Spike Roastery Again, you’ll not be short of options for a coffee subscription, but with Old Spike Roastery in Peckham you can also help tackle homelessness. One initiative is an eight-week training course that takes people off the streets and turns them into qualified baristas. In addition, 65% of all Old Spike’s profits go back into its social mission. From £6.95 per week.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion